** Where are Class Action Claims Against Consumer Food and Personal Product Companies Trending in 2016?**

By: Brent E. Johnson

We have blogged in the past about some of the “usual suspects” in the consumer class action line-up – particularly for food, beverage, cosmetics and related industries – for example, the “all-natural” case – the “evaporated cane juice” case – and the “handmade” or “craft beer” case. Trends come and go – as Plaintiffs run out of companies to sue and as companies change their labeling and advertising in response to the litigation risks.

We have blogged in the past about some of the “usual suspects” in the consumer class action line-up – particularly for food, beverage, cosmetics and related industries – for example, the “all-natural” case – the “evaporated cane juice” case – and the “handmade” or “craft beer” case. Trends come and go – as Plaintiffs run out of companies to sue and as companies change their labeling and advertising in response to the litigation risks.

Which begs the question: Where are the current litigation trends leading? We have surveyed recent filings to identify some of the tropes and traps that plaintiffs lawyers are currently focusing on:

As we have discussed in the past, the attractiveness of the all-natural class claim lies in the gaps between FDA guidance and labeling law and the vagaries of the reasonable consumer standard. That gap may be closing with the FDA taking comments and perhaps looking to expand its policy on “natural” foods. As the term “Natural” loses some of its vagueness, the term “healthy” appears to be taking its place – particularly in so far as the term has the required “eye of the beholder” quality necessary to support class action claims (although in some respects the term “healthy” is regulated see e.g., 21 CFR 101.65(d)(2)) . For example in Kaufman v. CVS Caremark Corp., No. 16-1199, 2016 WL 4608131, at *1 (1st Cir. Sept. 6, 2016) (reversing district court dismissal on Rule 12), CVS Pharmacy, Inc. was sued for its Vitamin E dietary supplement because its label touts the product as supporting “heart health.” Plaintiff argues that this is misleading because the medical literature does not support a link between consuming vitamin E and cardiovascular health. Kaufman v. CVS Caremark Corp., No. CV 14-216-ML, 2016 WL 347324, at *1 (D.R.I. Dkt. No. 1 at 7) (and in some studies cited by Plaintiff – Vitamin E dosage increases the rate of heart failure). In Hunter v. Nature’s Way Prod., LLC, No. 16CV532-WQH-BLM, 2016 WL 4262188, at *1 (S.D. Cal. Aug. 12, 2016) (denying motion to dismiss), Plaintiff alleges that Nature’s Way’s coconut oil is advertised with various health claims (such as its “Variety of Healthy Uses”, “ideal for exercise & weight loss programs”, “fuel a[] healthy lifestyle”), but according to Plaintiff, coconut oil products are not “healthy” . . . “but rather their consumption causes increased risk of CHD, stroke, and other morbidity.” (Dkt. No. 1-5 Compl. at ¶ 118). In Campbell v. Campbell Soup Co., No 3:16-cv-01005 (S.D. Cal. August 8, 2016) (Dkt 18) (Def. Mot. to Dismiss), Campbell’s Soup Co is defending against Plaintiff’s claims that its Healthy Request® soups are not “healthy” because they contains partially hydrogenated oil (PHO). Notably, Campbell’s soups are somewhat unique from other food labelling cases because they contain more than 2% meat or poultry and therefore are USDA regulated (see 21 U.S.C. § 451, et seq.) and their labelling is pre-approved (see 21 U.S.C. § 457; accord 21 U.S.C. § 607). Campbell’s has doubled-down on that argument – moving for Rule 11 sanctions. No 3:16-cv-01005 (S.D. Cal. August 29, 2016) (Dkt 18). In Lanovaz v. Twinings N. Am., Inc., No. 5:12-CV-02646-RMW (N.D. Cal. September 6, 2016) (dismissing remaining claims), Twinings successfully defended against claims that the labeling of its tea as a “healthy tea drinking experience” and having “antioxidant” benefits were misleading. In particular Plaintiff claimed that Twinings’ health benefits could not be substantiated and were contrary to FDA regulations. No. 5:12-CV-02646-RMW (N.D. Cal. Dkt. Nos. 1, 24). It appears that “Healthy” is the new “Natural.”

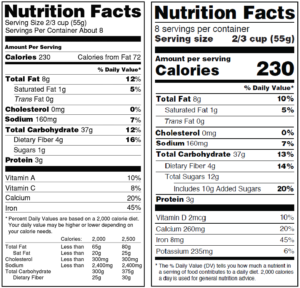

Plaintiff’s lawyers are also taking a close look at ingredients – to determine if touted anchor ingredients are prominent enough. For example in Coe v. Gen. Mills, Inc., No. 15-CV-05112-TEH, 2016 WL 4208287, at *1 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 10, 2016) (Order denying Mot. to Dismiss), Plaintiffs argued (successfully at the pleading stage) that General Mills’ Cheerios Protein product labeling is misleading because it implies that the product is essentially the same as normal Cheerios but with added protein. While Plaintiffs acknowledge that Cheerios Protein does have more protein than regular Cheerios (Plaintiffs calculate that 200 calories of Cheerios contains 6 grams of protein, whereas 200 grams of Cheerios Protein contains 6.4 or 6.7 grams of protein), they argue that this smidgen of an increase is so immaterial as to be misleading. In another example, in Nazari v. Gen. Mills, Inc., No. 2:16-cv-02015 (E.D. Cal. Aug. 23, 2016), the Plaintiff sued Target with a proposed class action alleging the retailer’s up & up™ Green Aloe Vera Gel lacks traces of Aloe Vera. Plaintiff alleges that while the product is labelled as an “aloe vera gel” with “pure aloe vera,” its laboratory testing (which it contends would have revealed acemannan, the key compound in aloe vera) could detect no active aloe ingredient. In another example, in Torrent v. Thierry Oliver., No. 2:15-cv-02511 (C.D. Cal. Sept. 2, 2016) (denying motion to dismiss), Plaintiff survived dismissal on claims that Natierra brand Himalania Goji berries are misleadingly labeled because they are not berries from the Himalayan mountain region in China – which was inferred by the “Himalania” brand name. In labelling, as in everything else, attention to detail counts.

We will update you on these trends as they progress.

Two putative class action lawsuits have been filed over cellulose in

Two putative class action lawsuits have been filed over cellulose in