FDA

Is The Writing On The Wall For Prop 65?

By: Brent E. Johnson

On October 12, 539 BC, Persian ruler Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon. According to the Biblical Book of Daniel, on the night before the overthrow, the Babylonian king, Belshazzar, witnessed the appearance of a mysterious hand, which wrote on a palace wall, “Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin.” Belshazzar called for Daniel to interpret the mysterious inscription. Daniel’s translation: “You have been weighed . . . and found wanting.” Is the same writing on the wall for Prop 65?

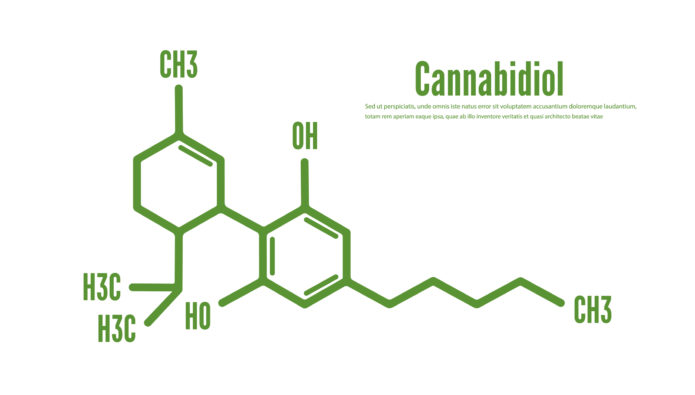

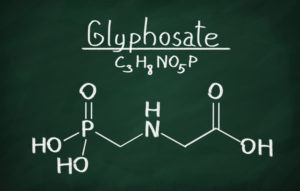

First came “Roundup.” As we’ve blogged about in the recent past, Monsanto, the manufacturer of the herbicide Roundup, filed a petition in Fresno County Superior Court to prevent the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (“OEHHA”) from listing glyphosate (the principle ingredient in Roundup) as a Prop 65 chemical requiring a warning label. Finding no success, Monsanto and several state agricultural associations moved to federal court seeking an order that they are not required to put a warning label on Roundup or food products containing glyphosate. While the federal case is ongoing, the court granted a preliminary injunction so that no warning is required during the pendency of the action. The federal court gave particular credence to Monsanto’s first amendment argument that it was being required to engage in commercial speech with which it did not agree. The court held that the State of California may only require commercial speakers to disclose “purely factual and uncontroversial information,” and the science before it was questionable regarding whether glyphosate is a carcinogen. In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (“IARC”) – a division of the World Health Organization — issued a report finding that glyphosate is a “probable carcinogen.” More recently, however, the Environmental Protection Agency issued a draft human health risk assessment that concluded that glyphosate is likely not carcinogenic. The federal case will put on trial the science behind OEHHA’s glyphosate listing, which is predicated exclusively on the IARC study.

After Roundup came coffee. As we’ve blogged about recently, in response to a ruling by the Los Angeles Superior Court that coffee must bear a Prop 65 cancer and reproductive harm warning, OEHHA announced, and opened a period for public comment on, a proposed regulation that would eliminate the need for cancer warnings on coffee products. OEHHA’s reasoning is illuminating: “In a review of more than 1,000 studies published this week, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) concluded that there is ‘inadequate evidence’ that drinking coffee causes cancer. IARC found that coffee is associated with reduced risk for cancers of the liver and uterus, and does not cause cancers of the breast, pancreas and prostate. IARC also found that coffee “exhibits strong antioxidant effects related to reduced cancer risk.” It seems that OEHHA is willing to look at coffee in its entirety — even though the Los Angeles Superior Court opinion and Prop 65, itself, focuses on the chemical alone. See Council for Education and Research on Toxics v. Starbucks Corp. et al., No. BC435759 (Cal. Super. Ct. L.A. County March 28, 2018)

And just this week, the California Court of Appeal (Second Appellate Division) ruled that breakfast cereal manufactures are not required to label their boxes with Prop 65 warnings based on the presence of acrylamide because federal law pre-empts Prop 65 when it comes to Fruity Pebbles. Post Foods, LLC v. Superior Court, No. B284057, 2018 WL 3424800, at *6 (Cal. Ct. App. July 16, 2018). The Court held that mandating a Prop 65 warning on cereals presented an “obstacle” to the Food and Drug Administration’s stated objective of encouraging the consumption of whole grains.

For those of us who practice in the food and beverage space, a finding of federal pre-emption of a state statute or regulation is the Holy Grail. In this case, the Court of Appeal found “obstacle pre-emption” by citing to correspondence between FDA and OEHHA in the early and mid-2000s regarding the application of Prop 65 to food, in general, and acrylamide, in particular. Specifically, in a July 14, 2003 letter from FDA Deputy Commissioner Lester Crawford to Joan Denton, Director of OEHHA, Commissioner Crawford stated:

“FDA is concerned that premature labeling of many foods with warnings about dangerous levels of acrylamide would confuse and could potentially mislead consumers, both because the labeling would be so broad as to be meaningless and because the risk of consumption of acrylamide in food is not yet clear. [¶] Furthermore, consumers may be misled into thinking that acrylamide is only a hazard in store-bought food. In fact, consumer exposure may be greater through home cooking. … In addition, a requirement for warning labels on food might deter consumers from eating foods with such labels. Consumers who avoid eating some of these foods, such as breads and cereals, may encounter greater risks because they would have less fiber and other beneficial nutrients in their diets. For these reasons, premature labeling requirements would conflict with FDA’s ongoing efforts to provide consumers with effective scientifically based risk communication to prevent disease and promote health.”

Post Foods, 2018 WL 3424800, at *2.

FDA’s letter should be read for what it is – a scathing indictment of Prop 65 as it pertains to food. FDA essentially told OEHHA: (1) Your Prop 65 labeling is so ubiquitous as to be “meaningless;” (2) Your science regarding acrylamide is suspect; and (3) Your labeling requirement is actually counterproductive because, to the extent consumers read the warnings, the labels might actually deter them from eating healthy foods, such as whole grains. FDA followed up with OEHHA in 2006 reaffirming its earlier position and observing that an acrylamide warning on food might “create unnecessary and unjustified public alarm about the safety of the food supply; dilute overall messages about healthy eating; and mislead consumers into thinking that acrylamide is only a hazard in store-bought food.”

These recent developments go to the core of several long-standing criticisms of Prop 65: (1) The science behind requiring a warning – in most cases, a study by IARC – is dubious; (2) The warning requirement is myopically focused on the presence of the accused chemical and does not take into account broader considerations of the value of the product as a whole or the actual risk posed by the presence of the chemical in the product; and (3) The “over-warning” engendered by Prop 65 dilutes the impact of consumer product warnings that are actually important. While Prop 65 apologists often resort to the argument that the law is “just a warning statute — it doesn’t ban products,” this argument glosses over the fundamental issue of what the warning actually means. Do the words “known to the State of California” mean that hard science supports the cancer or reproductive harm warning? Does the very presence of the chemical in the product actually increase the risk of cancer or reproductive harm to the consumer who uses it or consumes it? Does the product have benefits that outweigh any risks from exposure to the chemical?

These criticisms of Prop 65 finally have been heard by Congress, a group that was more than happy to legislate away Vermont’s GMO law, but heretofore has been disinclined to take on California. On June 18, 2018, a bipartisan group of congressmen introduced H.R. 6022 (“The Accurate Labels Act”), a bill “[t]o amend the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act to require that Federal and State mandated information declarations and labeling requirements applicable to the chemical composition of . . . consumer products meet minimum scientific standards to deliver accurate and clear information . . . .” Among the bill’s sponsors is Representative Jim Costa, a Democrat from California’s 16th Congressional District in the central San Joaquin Valley. The bill prohibits departments and agencies of the federal government as well as states and political subdivision of states from requiring information — including warnings — on consumer commodities unless, among other things, the information/warning is: (1) risk-based; (2) based on the best available science; and (3) based on an appropriate weight of the evidence review. Therefore, to the extent a Prop 65 chemical listing is based on the mere presence of the chemical in a product (i.e., not based on the risk of a particular exposure); is made purely because a single health organization (read, IARC) has determined that the chemical may be a carcinogen or reproductive toxicant; or does not weigh the risk/benefits of the chemical in particular products, the listing would run afoul of H.R. 6022. The bill also authorizes “[a]ny . . . person that is . . . required to display or communicate to a consumer covered information about a covered product, or is, or may be, subject to an enforcement action with respect to that requirement by a State or a political subdivision of a State, [to] bring a civil action in an appropriate district court of the United States against that State (or any private entity that is authorized to bring an enforcement action on behalf of that State) . . . if the requirement of the State or political subdivision does not comply with the requirements [of this Act].” If the bill becomes law, Bounty Hunters in California may find themselves the subject of federal lawsuits for making Prop 65 claims.

H.R. 6022 has been referred to the House Committee on Energy and Commerce. An analogous Senate bill, S 3109, is before the Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation. While these bills will have a difficult time making it out of committee because of timing issues and the likelihood of opposition from other California legislators in both houses, their very existence shows that Congress is paying attention. When coupled with the recent Roundup and acrylamide decisions, the House and Senate bills – like the mysterious inscription given to Belshazzar – may be the writing on the wall for Prop 65?

Round Up – Round One

** Monsanto Gets its First Victory in the Battle over Herbicide Prop 65 Listing **

By: Brent E. Johnson

Background: Glyphosate is a molecule that inhibits a biological process only found in plants (not humans and animals). The compound was discovered by a Monsanto chemist in 1970, then patented and brought to market in 1974 as “Round Up.” Initially, the product was only used on a small scale, because, while it is toxic to most weeds, it also kills most crops. However, when Monsanto developed and began introducing genetically modified crops engineered to be resistant to the herbicide (“Roundup Ready” crops), the chemical was able to be used on a broad scale. As a result, the chemical’s use skyrocketed — at the same time that overall herbicide use dropped. In 1987, only 11 million pounds of Round Up were used on U.S. farms – now nearly 300 million pounds are applied each year. A study published in 2015 in the journal Environmental Sciences Europe found that Americans have applied 1.8 million tons of glyphosate since its introduction in 1974. Worldwide, the number is 9.4 million tons. That is enough to spray nearly half a pound of Roundup on every cultivated acre of land in the world. Round Up and Round Up Ready products are worth many billions of dollars.

California’s Office of Environment Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) announced a proposed listing of glyphosate as a Prop 65 chemical on September 4, 2015. The effect of glyphosate’s listing under Prop 65, cannot be underestimated as there are detectable levels of glyphosate in virtually every part of the food chain. Monsanto is famously vigilant in protecting its rights – for example in protecting its crop patents. So when OEHHA proposed the listing, it was inevitable that litigation would follow.

On January 21, 2016, Monsanto struck. It filed a petition in Superior Court in Fresno County seeking injunctive and declaratory relief to enjoin OEHHA from listing glyphosate as a Prop 65 chemical. It did so on the basis of its allegation that the listing mechanism violated the California and United States Constitutions. See Monsanto Co. v. Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, No. 16-CE CG 00183, (Sup. Cal.) That is, primarily, Monsanto complained about how its product came to be added to the list.

Under Cal. Health & Safety Code § 25249.8 (b), which cites to Cal. Lab. Code § 6382 (b)(1), “at a minimum” the Prop 65 list must include those “[s]ubstances listed as human or animal carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).” IARC, based in Lyon, France, is an intergovernmental agency, part of the World Health Organization. In March 2015, IARC issued a report labeling the weed killer glyphosate as a “probable carcinogen.” Glyphosate Monograph, Vol. 112, IARC Monographs Series (IARC, 2015b). That report is not without controversy — for example, the EPA has more recently issued its draft human health risk assessment which concludes that glyphosate is not likely to be carcinogenic to humans. Nevertheless, OEHHA has interpreted § 25249.8 (b) to provide that once IARC lists a chemical, it is mandatory for them to do so also. OEHHA duly noticed its intent to list, prompting the lawsuit.

Monsanto raised four arguments, all ultimately rejected by the trial court.

- First, Monsanto argued that OEHHA unconstitutionally delegated its authority to the IRAC by relying on its assessment that glyphosate is a probable human carcinogen. The doctrine of nondelegation is the rather esoteric theory that one branch of government must not authorize another entity to exercise the power or function that it is constitutionally authorized to exercise, itself. Under California law, this doctrine is not offended if the legislature determines the overarching legislative policy and leaves to others the role of filling in the details. Monsanto Co. v. Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, 2017 WL 3784247 (Cal.Super.) citing Kugler v. Yocum, 69 Cal.2d 371, 375-376 (Cal. 1968). On that point, the court stated that the Prop 65 listing mechanism does not constitute an unconstitutional delegation of authority to an outside agency, since the voters and the Legislature have established the basic legislative scheme and policy and it was permitted to leave the “highly-technical, fact-finding” to the IARC (and other authoritative bodies referred to in the Act).

- Second, the court rejected Monsanto’s due process claims. It held that due processrights are only triggered by judicial or adjudicatory actions. California Gillnetters Assn. v. Department of Fish & Game, 39 Cal.App.4th 1145, 1160 (Cal. 1995). The court stated the Prop 65 listing was not adjudicative, but a “quasi-legislative act.”

- Third, the court rejected Monsanto’s arguments that the listing process violated California’s Article II, Section 12, which prohibits private corporations from holding office or performing legislative functions. It found that there are no facts that would tend to indicate that the IARC is a “private corporation,” or that IARC has an pecuniary interest in being given the power to name certain chemicals on its list of possible carcinogens.

- Fourth, the court gave short shrift to Monsanto’s claim that listing glyphosate would violate its right to free speech under the California and Federal constitutions, in particular the inherent protections for commercial speech from unwarranted governmental regulation. The court held that the First Amendment claim was not ripe for adjudication because the mere listing of glyphosate does not in and of itself require Monsanto to provide a warning and it may never be required to give a warning.

Monsanto appealed this ruling. It also sought a stay of the trial court’s decision pending its appeal, The appellate court and the California Supreme Court rejected these requests for a stay in June 2017. OEHHA wasted no time after the Supreme Court’s decision adding glyphosate to the list on July 7, 2017. After this ruling, subject to the substantive appeal of the trial court decision, July 7, 2018 was to be the date by which companies must comply with the Prop 65 requirements for glyphosate.

Not content to wait idly by, Monsanto moved the battle to Federal Court, On November 15, 2017, it filed a complaint for declaratory and injunctive relief in the Eastern District of California (No. 2:17-cv-02401-WBS-EFB) together with the National Association of Wheat Growers, National Corn Growers Association, United States Durum Growers Association, Western Plant Health Association, Missouri Farm Bureau, Iowa Soybean Association, South Dakota Agri-Business Association, North Dakota Grain Growers Association, Missouri Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Associated Industries of Missouri and the Agribusiness Association of Iowa. So far, the following have also signed on as amicus – the State of Wisconsin, South Dakota, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Michigan, Kansas, Louisiana, Iowa, Indiana, Idaho and Missouri.

The complaint starts by attacking the IARC listing, noting that a dozen other global regulatory and scientific agencies have found no link between glyphosate and cancer. The allegedly “false” warning under Prop 65, plaintiffs argue, compels speech violating Plaintiff’s First Amendment rights. Plaintiffs also argue that the listing and warning requirement conflict with, and are preempted by Federal legislation,notably the United States Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) and Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA). The complaint also raises the issue rejected by the state court that the listing process violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Plaintiffs filed a Motion for Preliminary Injunction on December 6, 2017, which was heard on February 20, 2018. On February 26, 2018, U.S. District Court Judge William B. Shubb ruled in favor of Monsanto and the other named plaintiffs. No. CV 2:17-2401 WBS EFB, 2018 WL 1071168, at *1 (E.D. Cal. Feb. 26, 2018). The order declined to go so far as to remove glyphosate from the Proposition 65 list, but at least for now, bars the State of California from imposing the corresponding warning requirement while the case challenging its listing proceeds on the merits.

The court primarily relied on Monsanto’s First Amendment argument in issuing the injunction. Judge Shubb concluded that, to the extent Prop 65 necessitates warnings for glyphosate, California is in essence compelling commercial speech. The court held that the government may only require commercial speakers to disclose “purely factual and uncontroversial information” about commercial products or services, as long as the “disclosure requirements are reasonably related” to a substantial government interest and are neither “unjustified [n]or unduly burdensome.” Id. at * 5 citing Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel of Supreme Court of Ohio, 471 U.S. 626, 651 (1985); CTIA-The Wireless Ass’n v. City of Berkeley, 854 F.3d 1105, 1118 (9th Cir. 2017).

In this case, the court held that the link between cancer and glyphosate was not uncontroverted – particularly where “only one health organization had found that the substance in question causes cancer and virtually all other government agencies and health organizations that have reviewed studies on the chemical had found there was no evidence that it caused cancer.” Id. at *6. The court went further stating, “[u]nder these facts, the message that glyphosate is known to cause cancer is misleading at best.” Id. Accordingly, it was determined that the balancing of interests involved weighed in favor of restraining the enforcement of the warning requirement for glyphosate while the remainder of the case was decided.

The court enjoined “defendants” (i.e. OEHHA and the California Attorney General) and “their agents and employees, all persons or entities in privity with them, and anyone acting in concert with them.” Id. at *8. We will see if private Prop 65 bounty hunters consider themselves bound by this injunction.

One area the dispute will also move to is the No Significant Risk Levels (NSRLs) for glyphosate. If the NSRL is set at a particularly high level (perhaps based on the factual controversies referred to above), then the issue over listing may be mooted. Again, however, a sky high NSRL still may not dissuade Prop 65 bounty hunters.

2018: Food Litigation Trends – Diet Claims

** Part I in our Series on the New Year of Food Litigation **

By: Brent E. Johnson

“Diet” advertising claims are a potential new target of consumer class actions that companies should be on the lookout for in 2018. A trio of cases filed in late 2017 against three of the largest “diet” branded beverage companies — The Coca-Cola Co., Pepsi-Cola Co. and Dr Pepper Snapple Group Inc. — highlight the risk. The complaints in these cases accuse the soda companies of violating the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, which prohibits the labeling of food that is “false or misleading in any particular.” 21 U.S.C. § 343(a). The cases were all filed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York: Excevarria v. Dr Pepper Snapple Group Inc. et al., 1:17-cv-07957 (S.D.N.Y, Oct. 16, 2017); Geffner. v. The Coca-Cola Co., 1:17-cv-07952 (S.D.N.Y, Oct. 16, 2017); and Manuel v. Pepsi-Cola Co., 1:17-cv-07955 (S.D.N.Y, Oct. 16, 2017).

Plaintiffs claim that inherent in “diet” branding is a promise that the product will assist with weight loss. The complaints allege that this promise is unfulfilled with diet sodas because the artificial sweeteners used in the defendants’ products cause weight gain, not weight loss.

The science referenced in the complaints (while still developing) is intriguing. We all know that reducing caloric intake is one of the foundations of weight loss. Starting in the 1960’s, beverage makers removed natural sugars (high in calories) from products, replacing them with newly discovered “low calorie” sweeteners such as aspartame and sucralose. These sweeteners have been rigorously tested and are generally regarded as safe by FDA. See 46 FR 38283, 48 FR 31376; see also Chobani, LLC v. Dannon Co., Inc., 157 F. Supp. 3d 190 (N.D.N.Y. 2016). More recently, though, these sweeteners have been tested for their efficacy in weight loss. In particular, a recent Yale study suggests that the caloric value of artificial sweeteners is immaterial – it is the sweetness of the products that matters. According to the study, a sweetness “mismatch” – where an intensely sweet product does not have the expected caloric load — causes the body to shut down metabolism. This lower metabolism in many cases causes weight gain.

But what does that mean for “diet” products containing artificial sweeteners? Is the simple use of the term “diet” (particularly where it is only in the brand name, i.e., Diet Coke, or Diet Pepsi) an affirmative representation that the soda is a weight-loss product? As with any false advertising lawsuit, “context is crucial.” Fink v. Time Warner Cable, 714 F.3d 739 (2d Cir. 2013). Is Diet Coke actually sold as a weight loss supplement? Does any reasonable consumer believe that soda (sugar free or not) will make them lose weight? Is “diet” in these contexts a relative term – i.e., as compared to a regular soda. And is “diet” (or similar terms such as “lite” or “low-cal”) too ambiguous and idiosyncratic to attach an absolute meaning as plaintiffs attempt to in these lawsuits? Is it the equivalent of suing McDonald’s because the Happy Meal does not actually make you “happy”?

The diet soda giants have one significant advantage in this debate. The use of the term “diet” in the brand name of soft drinks is grandfathered under the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990 (“NLEA”). Under the NLEA, the word “diet” is specifically approved as a brand name for a soda on the market in 1989 as long as the soda is under 40 calories per serving. 21 U.S.C. § 343(r)(2)(D) (requiring compliance with 21 C.F.R. § 105.66). And the NLEA does not mandate that the use of the word “diet” meet some “weight loss” requirement. FDA is otherwise silent, except for noting that “diet” branding must not be otherwise false and misleading. 21 C.F.R. § 101.13(q)(2). Arguably, the express grandfathering under the NLEA preempts or otherwise forecloses on an accusation that certain sodas cannot properly be branded “diet.”

How courts treat the “diet” claims will be an important issue to watch in 2018. If this concept of artificial-sweetener-as-diet-killer takes hold, it could be a rocky year for foods that make similar claims. We will be watching the “diet” wars with interest . . . and coming in Part II of our multi-part series – xantham gum as the basis of new “natural” class actions.

Closer to the End for the Natural Impasse?

** Congress Looking at FDA to Release All Natural Guidelines **

By: Brent E. Johnson

Set of watercolor green logo. Leaves, badges, branches wreath, plants elements. Hand drawn painting. Sign label,textured emblem set. Organic design template.

Are the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) “natural” guidelines imminent? As we have blogged about in the past, one well-worn path plaintiffs’ counsel have taken is to bring suit against a company using “natural” in its food labelling – set-up against plaintiff’s own particular (and sometime peculiar) definition of what a natural food or ingredient is. The absence of FDA guidance has given room to maneuver on both sides of the issue in “natural” litigation. In 2015, FDA opened a comment period on new regulations regarding the use of the term “natural” in food labeling, but there has been radio silence since (notwithstanding a growing volume of cases filed on the subject). Notably, in a recent bill report accompanying the Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies Appropriations Bill, 2018 (H.R. REP. 115-232, 1), the House Committee on Appropriations directed “FDA to provide a report within 60 days of enactment of this Act on the actions and timeframe for defining ‘natural’ so that there is a uniform national standard for the labeling claims and consumers and food producers have certainty about the meaning of the term.” H.R. Rep. No. 115-232, at 72 (2017). This appropriations bill, though formally introduced, remains pending in Congress – accordingly, the putative 60 day deadline for reporting to the committee has not yet commenced. Nonetheless, it is a good sign that the issue has the attention of Congress (and in particular the committee that controls funding). See discussion Rosillo v. Annie’s Homegrown Inc., No. 17-CV-02474-JSW, 2017 WL 5256345, at *3–4 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 17, 2017) (staying all natural case under primary jurisdiction doctrine).

No Love from FDA

**FDA Warns Bakery it Cannot Label “Love” As An Ingredient **

By: Brent E. Johnson

A warning letter published by the Food & Drug Administration and issued to Massachusetts-based Nashoba Brook Bakery highlights that FDA has little tolerance for eccentricity when it comes to labelling compliance. According to the letter, Nashoba sold granola with labeling that said that one of the ingredients was “love.” Charming as that may be, FDA was not impressed, writing that “Ingredients required to be declared on the label or labeling of food must be listed by their common or usual name . . . ‘Love’ is not a common or usual name of an ingredient, and is considered to be intervening material because it is not part of the common or usual name of the ingredient.” It is not clear whether FDA was inspired by 2016 research that found that study participants rated identical food as superior in taste and flavor if they were told it was lovingly prepared using a family-favorite recipe. We’ll see if there are any repercussions to the bakery from the FDA Love Letter – other than the free publicity it garnered.

For those who follow our blog, you’ll recall we have written in the past about KIND®, who was also on the receiving end of a not so kind letter asking the company to remove any mention of “healthy” from its packaging and website. Notably, later in 2016, the FDA had a change of heart – on April 22, 2016 emailing Kind informing the company that it could return to its “healthy” language – as long as the use of “healthy” is in relation to its “corporate philosophy,” and not a “nutrient claim” (the latter being the statutory predicate under 21 C.F.R. § 101.65). Unfortunately for Kind, the 2015 letter prompted a suite of lawsuits. A number were filed in California: Kaufer v. Kind LLC., No. 2:15-cv-02878 (C.D. Cal), Galvez v. Kind LLC., No. 2:15-cv-03082 (C.D. Cal); Illinois and New York: Cavanagh v. Kind, LLC., 1:15-cv-03699-WHP (S.D.N.Y.), Short et al v. Kind LLC, 1:15-cv-02214 (E.D.N.Y). Ultimately, a multi-district panel assigned the case to the Southern District of New York (In Re: Kind LLC “Healthy” and “All Natural” Litigation, 1:15-md-02645-WHP). The cases in large part were voluntarily withdrawn after FDA sent its April 22, 2016 “change of heart” email.

That said, plaintiffs in the MDL case also made claims that Kind Bars are not “All Natural.” The Court stayed the “All Natural” component of the action pending FDA’s consideration of the term under the primary jurisdiction doctrine. Dkt. No. 83 (see also our previous post on primary jurisdiction “all natural cases.”) Plaintiffs have recently sought to lift the stay, arguing that FDA is taking too long. Dkt. No. 109. Plaintiffs have also amended their “All Natural” claims to encompass the additional question of whether Kind’s “Non-GMO” statements comport with state GMO laws. Kind responded by arguing that such state law claims are preempted by the National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard, Pub. L. 114-216 (“National GMO Standard”) (7 U.S.C. § 1639i). Dkt. No. 101. The Court has heard oral argument on the GMO preemption issue and the lifting of the stay, but is yet to rule on either.

Healthy Conscious

** FDA Updating Requirements for “Healthy” Claims on Food Labeling **

By: Brent E. Johnson

One of the trending areas we have blogged about last year was “healthy” claims in food labelling becoming the new “all natural” target; see Hunter v. Nature’s Way Prod., LLC, No. 16CV532-WQH-BLM, 2016 WL 4262188, at *1 (S.D. Cal. Aug. 12, 2016) (Coconut Oil); Campbell v. Campbell Soup Co., No 3:16-cv-01005 (S.D. Cal. August 8, 2016) (Dkt 18) (Healthy Request® canned soups); Lanovaz v. Twinings N. Am., Inc., No. 5:12-CV-02646-RMW (N.D. Cal. September 6, 2016) (Twinings bagged tea). It is a lucrative area for the plaintiff’s bar. James Boswell et al. v. Costco Wholesale Corp., No. 8:16-cv-00278 (C.D. Cal) (recent $750,000 coconut oil settlement based on “healthy” labeling).

In many respects this trend was kicked off in 2015 by the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) who issued the KIND® company a not so kind letter asking the company, pursuant to 21 U.S.C. § 343(r)(1)(A) to remove any mention of the term “healthy” from its packaging and website. See our prior blog post. The basis for the FDA’s action is that the term “healthy” has specifically defined meanings under 21 CFR 101.65(d)(2) which includes objective measures such as saturated fat content (must be > 1 g) (see 21 CFR 101.62(c)(2)). Later in 2016 the FDA seemingly had a change of heart – emailing Kind and stating that the company can return the “healthy” language – as long use “healthy” is used in relation to its “corporate philosophy,” not as a nutrient claim.

Notably, this sparked a wider public health debate about the meaning of “healthy” and whether the focus, for example on the type of fat rather than the total amount of fat consumed, should be reconsidered in light of evolving science on the topic. In September 2016 the FDA issued a guidance document (Guidance for Industry: Use of the Term “Healthy” in the Labeling of Human Food Products) stating that FDA does not intend to enforce the regulatory requirements for products that use the term healthy if the food is not low in total fat, but has a fat profile makeup of predominantly mono and polyunsaturated fats.

The FDA also requested public comment on the “Use of the Term “Healthy” in the Labeling of Human Food Products” – which comment period ended this week. Comments poured in from consumers and industry stakeholders, reaching 1,100 before the period closed on April 26, 2017. The FDA has not provided a timeline as to when revisions to the definition of “healthy” might occur following these public comments – and it is not clear if President Donald Trump’s January executive order, requiring that two regulations be nixed for every new rule that is passed, will hinder the FDA’s ability to issue a rulemaking on the term “healthy” in the near future. It is also not clear whether the FDA will combine the rulemaking with its current musing of use of the term “natural” – as the terms are sometimes used synonymously. Industry groups (and the defense bar) are hopeful though that some clarity will come sooner rather than later.

Alert: Ninth Circuit Opens A Door For All Natural Class Claims

** Appeal Court Panel Holds That Genuine Dispute Remained As To Whether All Natural Claims Would Survive Reasonable Consumer Test **

By: Brent E. Johnson  Judge Lucy H. Koh gave all natural class defendants cause for celebration back in 2014 when she closed the door on a putative class representative’s claim that Dole’s fruit juices and fruit cups were wrongfully labelled as “All Natural.” Brazil v. Dole Packaged Foods, LLC, No. 12-CV-01831-LHK, 2014 WL 6901867 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 8, 2014). Last week, however, the Ninth Circuit re-opened that door slightly – at least enough for the plaintiffs’ bar to try to squeeze their feet in.

Judge Lucy H. Koh gave all natural class defendants cause for celebration back in 2014 when she closed the door on a putative class representative’s claim that Dole’s fruit juices and fruit cups were wrongfully labelled as “All Natural.” Brazil v. Dole Packaged Foods, LLC, No. 12-CV-01831-LHK, 2014 WL 6901867 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 8, 2014). Last week, however, the Ninth Circuit re-opened that door slightly – at least enough for the plaintiffs’ bar to try to squeeze their feet in.

Mr. Brazil alleged in his 2012 Complaint that Dole’s fruit cups and fruit juices were falsely labelled as “All Natural” because they contained citric acid (i.e. vitamin C) and ascorbic acid (used to prevent discoloring). Dole successfully argued on summary judgment that Plaintiff had failed to show that a significant portion of the consuming public or of targeted consumers, acting reasonably under the circumstances, would be misled by its labeling. Id. at *4, citing Lavie v. Procter & Gamble Co., 105 Cal.App. 4th 496, 507 (2003). Plaintiff’s own opinion about the added Vitamin C and absorbic acid was not enough. Id. Neither was his rationale that a reasonable consumer could be misled by virtue of a label that violated FDA guidance on the topic (the FDA is not a reasonable consumer and vice versa, Judge Koh reasoned). Further, in a prior ruling, Judge Koh decertified Plaintiff’s main damages class because Plaintiff’s damages model (or lack thereof) failed the threshold test of Comcast Corp. v. Behrend, 569 U.S. ___ (2013), i.e., that damages could be adequately calculated with proof common to the class. Brazil appealed both the summary judgment and decertification decisions.

The Ninth Circuit affirmed in part and reversed in part. Brazil v. Dole Packaged Foods, LLC, No. 14-17480, 2016 WL 5539863, at *1 (9th Cir. Sept. 30, 2016).

The good news is that the Ninth Circuit agreed with Judge Koh’s decertification of the damages class – and by so doing signaling that the Circuit will continue adhering to the Comcast principle that Plaintiffs have the burden of demonstrating a viable class-wide basis of calculating damages. It held that the lower court correctly limited damages to the difference between the prices customers paid and the value of the fruit they bought—in other words, the “price premium.” 2016 WL 5539863, at *2 – 3, citing In re Vioxx Class Cases, 103 Cal. Rptr. 3d 83, 96 (Cal. Ct. App. 2009). The Ninth Circuit reiterated that under the price premium theory, a plaintiff cannot be awarded a full refund unless the product she purchased was worthless – which in this case – the fruit was not. Id. citing In re Tobacco Cases II, 192 Cal. Rptr. 3d 881, 895 (Cal. Ct. App. 2015). Because Mr. Brazil did not (and presumably could not) explain how this premium could be calculated across a common class, the motion to decertify was rightly decided. Id. at *3.

The bad news is that the Appeals Court rejected the lower court’s reasoning that bare allegations of an individual’s claims of deception were insufficient to show the reasonable consumer would be equally deceived. Troublingly, the court used the FDA’s informal policy statement (see Janney v. Mills, 944 F. Supp. 2d 806, 812 (N.D. Cal. 2013) (citing 58 Fed. Reg. 2302–01)) on the issue as determinative of the reasonable consumer standard. As one commentator has noted, this converts informal guidance into binding authority.

With the damages class gone, the Ninth Circuit remanded the case for a determination of Plaintiff’s injunctive relief class. That may be a pyrrhic victory in the end. As we have blogged in the past, a plaintiff who is aware of the supposed deception is not in a position, as Pete Townshend penned, to be fooled again.