Food

Is The Writing On The Wall For Prop 65?

By: Brent E. Johnson

On October 12, 539 BC, Persian ruler Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon. According to the Biblical Book of Daniel, on the night before the overthrow, the Babylonian king, Belshazzar, witnessed the appearance of a mysterious hand, which wrote on a palace wall, “Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin.” Belshazzar called for Daniel to interpret the mysterious inscription. Daniel’s translation: “You have been weighed . . . and found wanting.” Is the same writing on the wall for Prop 65?

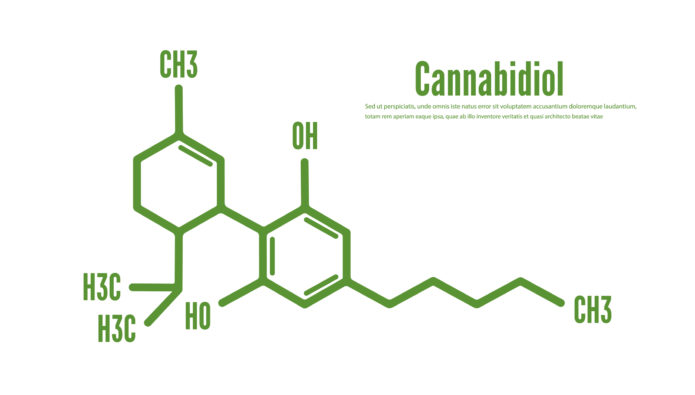

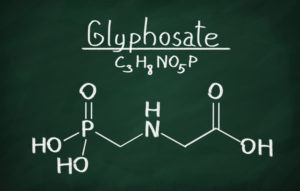

First came “Roundup.” As we’ve blogged about in the recent past, Monsanto, the manufacturer of the herbicide Roundup, filed a petition in Fresno County Superior Court to prevent the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (“OEHHA”) from listing glyphosate (the principle ingredient in Roundup) as a Prop 65 chemical requiring a warning label. Finding no success, Monsanto and several state agricultural associations moved to federal court seeking an order that they are not required to put a warning label on Roundup or food products containing glyphosate. While the federal case is ongoing, the court granted a preliminary injunction so that no warning is required during the pendency of the action. The federal court gave particular credence to Monsanto’s first amendment argument that it was being required to engage in commercial speech with which it did not agree. The court held that the State of California may only require commercial speakers to disclose “purely factual and uncontroversial information,” and the science before it was questionable regarding whether glyphosate is a carcinogen. In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (“IARC”) – a division of the World Health Organization — issued a report finding that glyphosate is a “probable carcinogen.” More recently, however, the Environmental Protection Agency issued a draft human health risk assessment that concluded that glyphosate is likely not carcinogenic. The federal case will put on trial the science behind OEHHA’s glyphosate listing, which is predicated exclusively on the IARC study.

After Roundup came coffee. As we’ve blogged about recently, in response to a ruling by the Los Angeles Superior Court that coffee must bear a Prop 65 cancer and reproductive harm warning, OEHHA announced, and opened a period for public comment on, a proposed regulation that would eliminate the need for cancer warnings on coffee products. OEHHA’s reasoning is illuminating: “In a review of more than 1,000 studies published this week, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) concluded that there is ‘inadequate evidence’ that drinking coffee causes cancer. IARC found that coffee is associated with reduced risk for cancers of the liver and uterus, and does not cause cancers of the breast, pancreas and prostate. IARC also found that coffee “exhibits strong antioxidant effects related to reduced cancer risk.” It seems that OEHHA is willing to look at coffee in its entirety — even though the Los Angeles Superior Court opinion and Prop 65, itself, focuses on the chemical alone. See Council for Education and Research on Toxics v. Starbucks Corp. et al., No. BC435759 (Cal. Super. Ct. L.A. County March 28, 2018)

And just this week, the California Court of Appeal (Second Appellate Division) ruled that breakfast cereal manufactures are not required to label their boxes with Prop 65 warnings based on the presence of acrylamide because federal law pre-empts Prop 65 when it comes to Fruity Pebbles. Post Foods, LLC v. Superior Court, No. B284057, 2018 WL 3424800, at *6 (Cal. Ct. App. July 16, 2018). The Court held that mandating a Prop 65 warning on cereals presented an “obstacle” to the Food and Drug Administration’s stated objective of encouraging the consumption of whole grains.

For those of us who practice in the food and beverage space, a finding of federal pre-emption of a state statute or regulation is the Holy Grail. In this case, the Court of Appeal found “obstacle pre-emption” by citing to correspondence between FDA and OEHHA in the early and mid-2000s regarding the application of Prop 65 to food, in general, and acrylamide, in particular. Specifically, in a July 14, 2003 letter from FDA Deputy Commissioner Lester Crawford to Joan Denton, Director of OEHHA, Commissioner Crawford stated:

“FDA is concerned that premature labeling of many foods with warnings about dangerous levels of acrylamide would confuse and could potentially mislead consumers, both because the labeling would be so broad as to be meaningless and because the risk of consumption of acrylamide in food is not yet clear. [¶] Furthermore, consumers may be misled into thinking that acrylamide is only a hazard in store-bought food. In fact, consumer exposure may be greater through home cooking. … In addition, a requirement for warning labels on food might deter consumers from eating foods with such labels. Consumers who avoid eating some of these foods, such as breads and cereals, may encounter greater risks because they would have less fiber and other beneficial nutrients in their diets. For these reasons, premature labeling requirements would conflict with FDA’s ongoing efforts to provide consumers with effective scientifically based risk communication to prevent disease and promote health.”

Post Foods, 2018 WL 3424800, at *2.

FDA’s letter should be read for what it is – a scathing indictment of Prop 65 as it pertains to food. FDA essentially told OEHHA: (1) Your Prop 65 labeling is so ubiquitous as to be “meaningless;” (2) Your science regarding acrylamide is suspect; and (3) Your labeling requirement is actually counterproductive because, to the extent consumers read the warnings, the labels might actually deter them from eating healthy foods, such as whole grains. FDA followed up with OEHHA in 2006 reaffirming its earlier position and observing that an acrylamide warning on food might “create unnecessary and unjustified public alarm about the safety of the food supply; dilute overall messages about healthy eating; and mislead consumers into thinking that acrylamide is only a hazard in store-bought food.”

These recent developments go to the core of several long-standing criticisms of Prop 65: (1) The science behind requiring a warning – in most cases, a study by IARC – is dubious; (2) The warning requirement is myopically focused on the presence of the accused chemical and does not take into account broader considerations of the value of the product as a whole or the actual risk posed by the presence of the chemical in the product; and (3) The “over-warning” engendered by Prop 65 dilutes the impact of consumer product warnings that are actually important. While Prop 65 apologists often resort to the argument that the law is “just a warning statute — it doesn’t ban products,” this argument glosses over the fundamental issue of what the warning actually means. Do the words “known to the State of California” mean that hard science supports the cancer or reproductive harm warning? Does the very presence of the chemical in the product actually increase the risk of cancer or reproductive harm to the consumer who uses it or consumes it? Does the product have benefits that outweigh any risks from exposure to the chemical?

These criticisms of Prop 65 finally have been heard by Congress, a group that was more than happy to legislate away Vermont’s GMO law, but heretofore has been disinclined to take on California. On June 18, 2018, a bipartisan group of congressmen introduced H.R. 6022 (“The Accurate Labels Act”), a bill “[t]o amend the Fair Packaging and Labeling Act to require that Federal and State mandated information declarations and labeling requirements applicable to the chemical composition of . . . consumer products meet minimum scientific standards to deliver accurate and clear information . . . .” Among the bill’s sponsors is Representative Jim Costa, a Democrat from California’s 16th Congressional District in the central San Joaquin Valley. The bill prohibits departments and agencies of the federal government as well as states and political subdivision of states from requiring information — including warnings — on consumer commodities unless, among other things, the information/warning is: (1) risk-based; (2) based on the best available science; and (3) based on an appropriate weight of the evidence review. Therefore, to the extent a Prop 65 chemical listing is based on the mere presence of the chemical in a product (i.e., not based on the risk of a particular exposure); is made purely because a single health organization (read, IARC) has determined that the chemical may be a carcinogen or reproductive toxicant; or does not weigh the risk/benefits of the chemical in particular products, the listing would run afoul of H.R. 6022. The bill also authorizes “[a]ny . . . person that is . . . required to display or communicate to a consumer covered information about a covered product, or is, or may be, subject to an enforcement action with respect to that requirement by a State or a political subdivision of a State, [to] bring a civil action in an appropriate district court of the United States against that State (or any private entity that is authorized to bring an enforcement action on behalf of that State) . . . if the requirement of the State or political subdivision does not comply with the requirements [of this Act].” If the bill becomes law, Bounty Hunters in California may find themselves the subject of federal lawsuits for making Prop 65 claims.

H.R. 6022 has been referred to the House Committee on Energy and Commerce. An analogous Senate bill, S 3109, is before the Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation. While these bills will have a difficult time making it out of committee because of timing issues and the likelihood of opposition from other California legislators in both houses, their very existence shows that Congress is paying attention. When coupled with the recent Roundup and acrylamide decisions, the House and Senate bills – like the mysterious inscription given to Belshazzar – may be the writing on the wall for Prop 65?

OEHHA Flips on Coffee

** California Regulators Propose New Regulation That Excludes Coffee Makers from Acrylamide Prop 65 Warning **

By: Brent E. Johnson

As we blogged about recently, Defendants in the blockbuster Prop 65 case, Council for Education and Research on Toxics v. Starbucks Corp. et al., No. BC435759 (Los Angeles County Superior Court), argued that although acrylamide was listed as a Prop 65 chemical – and although acrylamide was present in coffee (created as part of the roasting process) – consuming coffee, itself, has not been shown to cause cancer and, therefore, a Prop 65 warning was unwarranted. Defendants went further, arguing that studies have actually shown that coffee reduces the risk of some cancers. The court disagreed with Defendants analysis, holding that the relevant question was whether acrylamide causes cancer – not coffee as a whole. The court also rejected Defendants’ arguments touting the overall health benefits of coffee, which would have permitted the court to apply a “public health” exception to Prop 65 labeling.

The result: coffee sellers in California have no choice but to label their beverages with a Prop 65 warning. With millions of coffee drinkers in California – most of them daily drinkers – the Prop 65 warning looks to become even more ubiquitous (and ignored).

But not so fast! The California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) just proposed a new regulation providing that cancer warnings would not be required for coffee, stating (in effect) that the health benefits of consuming coffee outweigh the cancer risk posed by acrylamide. OEHHA’s press release articulates that its proposed regulation is based on scientific evidence that drinking coffee has not been shown to increase the risk of cancer and may reduce the risk of some types of cancer: “In a review of more than 1,000 studies published this week, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) concluded that there is ‘inadequate evidence’ that drinking coffee causes cancer. IARC found that coffee is associated with reduced risk for cancers of the liver and uterus, and does not cause cancers of the breast, pancreas and prostate. IARC also found that coffee “exhibits strong antioxidant effects related to reduced cancer risk.” OEHHA’s Initial Statement of Reasons are linked here and make for interesting reading. The proposed regulation, which would fit under § 25704 of the implementing regulations, states: “Exposures to listed chemicals in coffee created by and inherent in the processes of roasting coffee beans or brewing coffee do not pose a significant risk of cancer.”

OEHHA’s approach to this proposed regulation is identical to that rejected by the court in the Starbucks case when it denied the coffee sellers’ request that it consider the wider science on the cancer risks/benefits of coffee rather than the limited question of harm from acrylamide. It is also an interesting development in so far as Prop 65 (Cal. Health & Safety Code § 25249.8 (a)) requires OEHHA to list chemicals that IARC identifies as carcinogenic but does not have a mechanism for exempting those products that IARC gives a green light.

OEHHA’s proposed regulation begs the question: What about other products that are inherently healthy but contain a Prop 65 chemical? For example, lead appears in trace amounts in dietary supplements that are made from botanicals. Should these supplements also get their own product-specific exemption from Prop 65 labeling?

Attempts to Enforce “Humane” Treatment of Poultry Fail

** Foster Farms Prevail in Dismissing Class Action **

By: Brent E. Johnson

Resolving a politically-charged case based strictly on legal precedent and the evidence is no easy task. But as Elle Woods said (quoting Aristotle), “The law is reason free from passion.” (Granted, Elle disagreed with Ari.) Recently, a case involving the treatment of chicken broilers during the farming and slaughtering process posed that very dilemma to a superior court judge in Los Angeles. Leining v. Foster Poultry Farms, Inc., Cal. Super. Ct., No. BC588004.

The origins of this putative class action were both public and explosive. On June 17, 2015, reporters gathered at the Millennium Biltmore Hotel in downtown Los Angeles to view three minutes of video footage of animal cruelty perpetrated by Foster Poultry Farms, Inc. employees at two facilities in Fresno during the preceding two months. None other than noted animal welfare activist, vegetarian and retired “The Price Is Right” host, Bob Barker, narrated the video and spoke to the assembled reporters.

The video was shot by two undercover investigators from Mercy For Animals, a non-profit organization dedicated to advocating for animals generally and the prevention of farm animal cruelty specifically. The investigators applied for and obtained jobs with Foster Farms in order to surreptitiously record the footage. One of the investigators allegedly reported the animal abuse to his superior as well as phoned Foster Farms’ hotline to no avail.

Foster Farms was not the only party in Mercy For Animals’ crosshairs. Part of the focus of the presentation – and, in particular, Mr. Barker’s remarks – was the American Humane Association (“American Humane”), a non-profit whose website declares “is committed to ensuring the safety, welfare and well-being of animals.” American Humane pioneered, among other things, Hollywood’s animal welfare program, “No Animals Were Harmed.” In the case of farm animals, American Humane operates a voluntary certification program where farms can earn the American Humane Certified™ label through annual facility audits that demonstrate the farms’ compliance with American Humane’s animal welfare standards. Foster Farms had been Humane Certified™ for the two years preceding the May/June 2015 videotaped incidents. Mr. Barker informed the reporters that he had in years past been an advocate for American Humane until “I was suddenly made aware of what [American Humane] really [is], and I have absolutely no respect for [them]. I think they have failed miserably in their efforts to protect animals in the movie industry, and obviously they have failed miserably in any protection for animals in the food industry.” Mr. Barker went so far as to remark that American Humane once had been a beneficiary of his will — but given that he appears to be immortal, the loss of this status may not be a matter of consequence.

After the exposé at the Biltmore, Mercy For Animals filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission against both Foster Farms and American Humane claiming that the two entities had engaged in unfair and deceptive practices in connection with the advertising of Foster Farms chicken products under the Humane Certified™ label when the video footage showed that chickens were not being raised or slaughtered humanely. A week later, Foster Farms was sued for false advertising in a putative class action in Los Angeles County Superior Court. Leining v. Foster Poultry Farms, Inc., American Humane Association, BC588004 (LA Sup. Court, July 13, 2015). American Humane was added as a defendant by way of Plaintiff’s first amended complaint.

Foster Farms’ reaction to the publication of the video was swift. It suspended (and ultimately terminated) five employees allegedly involved in the animal cruelty and cooperated with the Fresno County Sheriff’s Department’s Agricultural Crimes Task Force. (At least one former employee was prosecuted.) In addition, Foster Farms reinforced “animal welfare training companywide and in its plants.” Finally, the Company implemented a state-of-the-art video monitoring system at its facilities that allowed auditors to review daily footage to assure employee compliance with Foster Farm’s animal welfare policies and procedures.

American Humane’s initial response to the Mercy For Animals video was surprise. Organization officials immediately met with Foster Farms to discuss the matter. After the meeting, American Humane’s spokesperson, Mark Stubis, stated, “Foster Farms has worked very hard to create a culture of humane treatment . . . . In the three years that we’ve been working with them, they have never failed an audit. This is an extremely rare situation for us.” Mr. Stubis continued, “The certification program can’t stop one or two employees who break those rules . . . . We certainly expect any certified farm to take immediate corrective action against anyone who abuses animals.” American Humane subsequently conducted unannounced inspections of Foster Farm’s poultry facilities and they passed. Foster Farms retained its status as Humane Certified™.

The FTC resolved the complaint filed by Mercy For Animals on April 28, 2016. In the FTC’s eyes, the issue revolved around its Guides Concerning the Use of Testimonials and Endorsements in Advertisements (“Endorsement Guides”). 16 C.F.R. § 255.4 “Because [American Humane] holds itself out as a bona fide independent certification organization, the [Humane Certified™] label on Foster Farms products arguably constitutes an endorsement, as defined by the FTC Guides Concerning the Use of Testimonials and Endorsements in Advertisements.” But despite its reference to the Endorsement Guides and its recitation of the general parameters of American Humane’s certification program, the FTC passed on the issue of whether or not the program resulted in a certification that “conveyed any express or implied representation that would be deceptive if made directly by the advertiser.” In the end, the FTC simply concluded that because Foster Farms took immediate remedial actions after learning of the video (suspending/terminating the involved employees, cooperating with law enforcement, and installing an expensive camera system) and passed American Humane’s inspections of the affected facilities, it would not recommend enforcement action “[d]espite concerns about the [American Humane] certification in light of the documented animal abuse . . . .”

Despite the FTC’s decision, the class action in Los Angeles raged on. The putative class was represented by Drinker Biddle & Reath, LLP (“DrinkerBiddle”) — a firm noted for its defense of consumer class actions. Perhaps not coincidentally, DrinkerBiddle represented the producers of The Price Is Right in past employment lawsuits brought by former Price is Right models.

The class action complaint did not place much emphasis on the Mercy For Animals video. Rather, the complaint’s gravamen was that American Humane’s certification standards were woefully inadequate and far from what a reasonable consumer would believe is the humane treatment of chickens – even chickens whose destiny is dinner. In Plaintiff’s graphic words, “(a) the chickens were hatched from eggs taken from facilities that are allowed to engage in forced-molting[1], maceration[2], beak-trimming[3], de-combing[4], toe amputation[5], food and water deprivation[6], and Noz Bonz practices[7]; (b) the chickens are shackled upside down by their feet for 90 seconds prior to slaughter as they are conveyed through processing facilities, electrically shocked before being rendered effectively unconscious, if they are at all, by such electric ‘stunning,’ and are then drowned and scalded, after having their necks cut, while they are, in at least some cases, still conscious; (c) the chickens suffer bruises and broken wings and bones; and (d) that the chickens spend their entire lives in chronic pain due to joint and leg deformities resulting from selective breeding for rapid growth, and live exclusively indoors in overcrowded poultry barns with high ammonia concentrations, many suffering from foot diseases, and unable to walk more than 5 feet without severe pain.” According to Plaintiff, because American Humane’s certification purportedly permitted these practices, the Humane Certified™ label was objectively false and misleading. [Editors’ Note: If Plaintiff’s allegation that some of the chickens were “drowned” – i.e., still breathing when they were placed in the scalding tank to remove their feathers – this would be a violation of United States Department of Agriculture regulations that would have presumably been discovered during Food Safety and Inspection Service inspections. The opinion does not reference any such evidence being presented to the court.]

On August 11, 2017, Foster Farms and American Humane filed for summary judgment Two weeks ago, the Honorable John Shepard Wiley, Jr. granted the defendants’ motion and dismissed the case. Judge Wiley’s opinion is an interesting and important read. It starts with the premise that American Humane’s certification is subjective. “The undisputed evidence in this record is that the word ‘humane’ is very vague.” Judge Wiley then moves to the controlling California authority, Hanberry v. Hearst Corp. (1969) 276 Cal.App.2d 680, a case where the plaintiff claimed that a pair of shoes bearing the “Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval” was slippery on vinyl flooring, which slipperiness caused her injury. The Hanberry Court concluded, according to Judge Wiley, that for a subjective product endorsement to be non-negligent, it must meet three requirements: (1) the endorser must be independent; (2) the endorser must take reasonable steps in conducting its evaluation; and (3) the evaluation must involve some degree of expertise. Id. at 686.

Judge Wiley dispatched with these requirements in short order. American Humane was independent from Foster Farms despite the fact that the Company allegedly pays American Humane $375,000 for its certification, which Plaintiff contended was “unusually high” (without evidentiary support such as comparisons to other similar organizations). As for Plaintiff’s assertion that American Humane was not independent because every certification program participant passed the organization’s audits, the court observed that the program is voluntary and, therefore, only those poultry farms that will pass the audits apply for the certification. “When the applicant pool is highly non-random, one cannot expect certification results to vary randomly.”

On the issue of reasonable steps, Judge Wiley dismissed Plaintiff’s assertion that conducting audits – as opposed to annual visits to each poultry facility – was required. “The Hanberry case condoned sampling, as is rational.” And the fact that American Humane gave poultry producers between seven and fourteen days’ notice of the audit did not create a “Potemkin Village” because “[n]otice was necessary to ensure there were actually chickens at that facility.”

Reading the opinion as a whole, though, it is clear that Plaintiff’s case ground ashore on the rocks of expert opinion. American Humane’s primary witness and Scientific Advisory Committee member was Dr. Joy Mench, who the Court described as “a leading expert on poultry who sits on virtually every scientific advisory board in the industry.” She was a professor at the University of Maryland and, later, the University of California Davis. Dr. Mench authored the only textbook in the field of poultry behavior and welfare. Most significant to Judge Wiley, Dr. Mench’s advisory committee work (including her work with American Humane) was truly independent – as it was without compensation other than travel expenses.

Pitted against Dr. Mench was Plaintiff’s expert, Leah Garces, USA Director for Compassion in World Farming and a member of the Board of Directors for Global Animal Partnership (https://www.compassioninfoodbusiness.com/our-work/meet-the-team/leah-garces/) whose testimony the Court struck in its entirety. Garces opined that American Humane’s standards are not “the best,” which Judge Wiley found irrelevant because American Humane does not represent that its standards are the best. Most tellingly, the Court characterized Plaintiff’s expert as follows: “Garces is a partisan advocate. . . . Garces is not a scholar or researcher. She has done no research and published no peer-reviewed articles or books. She has no scholarly or academic appointments or affiliations.” The Court’s final blow: “Garces’ method is ipse dixit: ‘I say it. Believe it.’ . . . Garces includes three vague sentences about her supposed professional experience, but nothing concrete distinguishes her from an opinionated but insubstantial dilettante.” Let’s face it, it’s hard to prevail when your expert’s testimony is dismissed as coming from a “dilettante” and excluded in its entirety.

What can we learn from the Foster Farms case? First, hire an expert with solid credentials. But putting aside the obvious, this case is interesting for what Defendants did not argue and what Plaintiff failed to argue. Although Dr. Mench testified that the word “humane” as it applies to the treatment of broiler chickens is “subjective” and the Court agreed, Defendants did not assert that the Humane Certified™ label was “puffery,” i.e., a claim that expresses subjective rather than objective views that no reasonable person would take literally. Newcal Indus., Inc. v. IKON Office Solutions, 513 F.3d 1038, 1053 (9th Cir. 2008). First, American Humane’s certification is an actual label that obviously has value or it wouldn’t exist. And second, consumers care that the animals they eat were treated humanely – even if their view of what “humane” means differs. For Plaintiff’s part, the question is: Where was the survey evidence demonstrating that, no matter how divergent consumer definitions of “humane” may be, American Humane’s standards do not meet their expectations? Granted, divergent views on the meaning of “humane” could prove challenging to class certification. But Plaintiff’s reliance on expert testimony regarding the expert’s personal definition of the term was unpersuasive – particularly when compared to the Defendants’ expert whose entire career has been focused on animal behavior and the humane treatment of same.

In the end, it appears that Plaintiff and her counsel relied on the “Parade of Horribles.” It didn’t work. The court analyzed the evidence that was before it and controlling California authority on commercial endorsements and determined that Plaintiff failed to meet her burden of showing a triable issue of fact that an independent, non-profit’s standard for the humane treatment of poultry, which was developed by members with expertise on the behavior of chickens and enforced through a reasonable auditing process, was somehow divergent from the reasonable consumer’s subjective view of the humane treatment of chickens.

Perhaps that is for the best. Consumer class actions are poor vehicles for recognizing and enforcing important substantive rights – including the rights of animals to humane treatment. Plaintiff’s complaint alleged that “the price of Foster Farms American Humane® Certified labeled chicken was $5.99/lb. whereas other chicken labeled ‘all natural’ but without the American Humane® Certified label was $2.99/lb. and other chicken labeled as ‘hatched, raised, harvested in the U.S.’ was $3.99/lb.” But would an advertising injunction and a $2-$3 refund per pound of chicken (up to ten pounds with receipt/5 pounds without) really have meant anything? The forum for such issues is not the Los Angeles County Superior Court, but Congress, the United States Department of Agriculture and state agriculture departments. Congress long ago enacted laws for the humane slaughter of livestock, 48 U.S.C. § 1901 et seq., and FSIS has promulgated detailed regulations under that law. But those regulations do not apply to poultry. With regard to chickens and other domestic fowl, FSIS regulations and inspections are directed to “good commercial practices,” rather than humane practices. Whether that changes as consumers demand and expect humane treatment of all animals raised for meat remains to be seen – but it’s certainly likely.

[1] Forced molting is the practice of forcing feather loss and regrowth, which increases egg production in mature hens. It is accomplished by withholding food (and sometimes water) from chickens for an extended period of time.

[2] Grinding up day-old male chicks because they will not lay eggs and are not suitable for meat production.

[3] Prevents chickens from injuriously pecking each other or themselves.

[4] De-combing is the removal of the chicken’s comb to limit the damage caused by frostbite or other injuries, to prevent the chicken’s head from becoming so heavy it interferes with eating or causes the head to sink into the chest, and to prevent injuries from other chickens or enclosures.

[5] Toe amputation occurs when a chicken’s toes are infected or suffer injury, such as frostbite.

[6] See footnote 1 on forced molting.

[7] According to the complaint, “the practice of piercing the nasal septum of young breeding roosters with a plastic stick to prevent them from accessing females’ food.”

Round Up – Round One

** Monsanto Gets its First Victory in the Battle over Herbicide Prop 65 Listing **

By: Brent E. Johnson

Background: Glyphosate is a molecule that inhibits a biological process only found in plants (not humans and animals). The compound was discovered by a Monsanto chemist in 1970, then patented and brought to market in 1974 as “Round Up.” Initially, the product was only used on a small scale, because, while it is toxic to most weeds, it also kills most crops. However, when Monsanto developed and began introducing genetically modified crops engineered to be resistant to the herbicide (“Roundup Ready” crops), the chemical was able to be used on a broad scale. As a result, the chemical’s use skyrocketed — at the same time that overall herbicide use dropped. In 1987, only 11 million pounds of Round Up were used on U.S. farms – now nearly 300 million pounds are applied each year. A study published in 2015 in the journal Environmental Sciences Europe found that Americans have applied 1.8 million tons of glyphosate since its introduction in 1974. Worldwide, the number is 9.4 million tons. That is enough to spray nearly half a pound of Roundup on every cultivated acre of land in the world. Round Up and Round Up Ready products are worth many billions of dollars.

California’s Office of Environment Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) announced a proposed listing of glyphosate as a Prop 65 chemical on September 4, 2015. The effect of glyphosate’s listing under Prop 65, cannot be underestimated as there are detectable levels of glyphosate in virtually every part of the food chain. Monsanto is famously vigilant in protecting its rights – for example in protecting its crop patents. So when OEHHA proposed the listing, it was inevitable that litigation would follow.

On January 21, 2016, Monsanto struck. It filed a petition in Superior Court in Fresno County seeking injunctive and declaratory relief to enjoin OEHHA from listing glyphosate as a Prop 65 chemical. It did so on the basis of its allegation that the listing mechanism violated the California and United States Constitutions. See Monsanto Co. v. Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, No. 16-CE CG 00183, (Sup. Cal.) That is, primarily, Monsanto complained about how its product came to be added to the list.

Under Cal. Health & Safety Code § 25249.8 (b), which cites to Cal. Lab. Code § 6382 (b)(1), “at a minimum” the Prop 65 list must include those “[s]ubstances listed as human or animal carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).” IARC, based in Lyon, France, is an intergovernmental agency, part of the World Health Organization. In March 2015, IARC issued a report labeling the weed killer glyphosate as a “probable carcinogen.” Glyphosate Monograph, Vol. 112, IARC Monographs Series (IARC, 2015b). That report is not without controversy — for example, the EPA has more recently issued its draft human health risk assessment which concludes that glyphosate is not likely to be carcinogenic to humans. Nevertheless, OEHHA has interpreted § 25249.8 (b) to provide that once IARC lists a chemical, it is mandatory for them to do so also. OEHHA duly noticed its intent to list, prompting the lawsuit.

Monsanto raised four arguments, all ultimately rejected by the trial court.

- First, Monsanto argued that OEHHA unconstitutionally delegated its authority to the IRAC by relying on its assessment that glyphosate is a probable human carcinogen. The doctrine of nondelegation is the rather esoteric theory that one branch of government must not authorize another entity to exercise the power or function that it is constitutionally authorized to exercise, itself. Under California law, this doctrine is not offended if the legislature determines the overarching legislative policy and leaves to others the role of filling in the details. Monsanto Co. v. Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, 2017 WL 3784247 (Cal.Super.) citing Kugler v. Yocum, 69 Cal.2d 371, 375-376 (Cal. 1968). On that point, the court stated that the Prop 65 listing mechanism does not constitute an unconstitutional delegation of authority to an outside agency, since the voters and the Legislature have established the basic legislative scheme and policy and it was permitted to leave the “highly-technical, fact-finding” to the IARC (and other authoritative bodies referred to in the Act).

- Second, the court rejected Monsanto’s due process claims. It held that due processrights are only triggered by judicial or adjudicatory actions. California Gillnetters Assn. v. Department of Fish & Game, 39 Cal.App.4th 1145, 1160 (Cal. 1995). The court stated the Prop 65 listing was not adjudicative, but a “quasi-legislative act.”

- Third, the court rejected Monsanto’s arguments that the listing process violated California’s Article II, Section 12, which prohibits private corporations from holding office or performing legislative functions. It found that there are no facts that would tend to indicate that the IARC is a “private corporation,” or that IARC has an pecuniary interest in being given the power to name certain chemicals on its list of possible carcinogens.

- Fourth, the court gave short shrift to Monsanto’s claim that listing glyphosate would violate its right to free speech under the California and Federal constitutions, in particular the inherent protections for commercial speech from unwarranted governmental regulation. The court held that the First Amendment claim was not ripe for adjudication because the mere listing of glyphosate does not in and of itself require Monsanto to provide a warning and it may never be required to give a warning.

Monsanto appealed this ruling. It also sought a stay of the trial court’s decision pending its appeal, The appellate court and the California Supreme Court rejected these requests for a stay in June 2017. OEHHA wasted no time after the Supreme Court’s decision adding glyphosate to the list on July 7, 2017. After this ruling, subject to the substantive appeal of the trial court decision, July 7, 2018 was to be the date by which companies must comply with the Prop 65 requirements for glyphosate.

Not content to wait idly by, Monsanto moved the battle to Federal Court, On November 15, 2017, it filed a complaint for declaratory and injunctive relief in the Eastern District of California (No. 2:17-cv-02401-WBS-EFB) together with the National Association of Wheat Growers, National Corn Growers Association, United States Durum Growers Association, Western Plant Health Association, Missouri Farm Bureau, Iowa Soybean Association, South Dakota Agri-Business Association, North Dakota Grain Growers Association, Missouri Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Associated Industries of Missouri and the Agribusiness Association of Iowa. So far, the following have also signed on as amicus – the State of Wisconsin, South Dakota, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Michigan, Kansas, Louisiana, Iowa, Indiana, Idaho and Missouri.

The complaint starts by attacking the IARC listing, noting that a dozen other global regulatory and scientific agencies have found no link between glyphosate and cancer. The allegedly “false” warning under Prop 65, plaintiffs argue, compels speech violating Plaintiff’s First Amendment rights. Plaintiffs also argue that the listing and warning requirement conflict with, and are preempted by Federal legislation,notably the United States Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) and Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA). The complaint also raises the issue rejected by the state court that the listing process violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Plaintiffs filed a Motion for Preliminary Injunction on December 6, 2017, which was heard on February 20, 2018. On February 26, 2018, U.S. District Court Judge William B. Shubb ruled in favor of Monsanto and the other named plaintiffs. No. CV 2:17-2401 WBS EFB, 2018 WL 1071168, at *1 (E.D. Cal. Feb. 26, 2018). The order declined to go so far as to remove glyphosate from the Proposition 65 list, but at least for now, bars the State of California from imposing the corresponding warning requirement while the case challenging its listing proceeds on the merits.

The court primarily relied on Monsanto’s First Amendment argument in issuing the injunction. Judge Shubb concluded that, to the extent Prop 65 necessitates warnings for glyphosate, California is in essence compelling commercial speech. The court held that the government may only require commercial speakers to disclose “purely factual and uncontroversial information” about commercial products or services, as long as the “disclosure requirements are reasonably related” to a substantial government interest and are neither “unjustified [n]or unduly burdensome.” Id. at * 5 citing Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel of Supreme Court of Ohio, 471 U.S. 626, 651 (1985); CTIA-The Wireless Ass’n v. City of Berkeley, 854 F.3d 1105, 1118 (9th Cir. 2017).

In this case, the court held that the link between cancer and glyphosate was not uncontroverted – particularly where “only one health organization had found that the substance in question causes cancer and virtually all other government agencies and health organizations that have reviewed studies on the chemical had found there was no evidence that it caused cancer.” Id. at *6. The court went further stating, “[u]nder these facts, the message that glyphosate is known to cause cancer is misleading at best.” Id. Accordingly, it was determined that the balancing of interests involved weighed in favor of restraining the enforcement of the warning requirement for glyphosate while the remainder of the case was decided.

The court enjoined “defendants” (i.e. OEHHA and the California Attorney General) and “their agents and employees, all persons or entities in privity with them, and anyone acting in concert with them.” Id. at *8. We will see if private Prop 65 bounty hunters consider themselves bound by this injunction.

One area the dispute will also move to is the No Significant Risk Levels (NSRLs) for glyphosate. If the NSRL is set at a particularly high level (perhaps based on the factual controversies referred to above), then the issue over listing may be mooted. Again, however, a sky high NSRL still may not dissuade Prop 65 bounty hunters.

Playing Chicken with the USDA

** Consumer Groups allege Chicken was laced with “Special K” in False Advertising Case **

By: Brent E. Johnson

The “Food Court” (aka the Northern District of California) has seen many unique lawsuits over the years, some of which we have reported on. Currently pending before the court is a must-watch dispute between Sanderson Farms Inc. (the #3 poultry producer in the U.S.) and three consumer and environmental non-profits — not only because of the bitter feud between the parties, but because of the fascinating intersection between a relatively unknown USDA program and its overseers and consumer expectations of what “100% Natural” means in the advertisement of meat products.

The battle began on June 22, 2017, when Organic Consumers Association, Friends of the Earth, and Center for Food Safety filed suit, on behalf of themselves and the general public, against Sanderson claiming that testing conducted by the Food Safety and Inspection Service (“FSIS”) of the United States Department of Agriculture (“USDA”) in 2015 and 2016 under the National Residue Program showed that Sanderson’s chicken “contain[s] residues of antibiotics important for human medicine, residues of veterinary antibiotics, and other pharmaceuticals, as well as residues of hormones, steroids, and pesticides.” Organic Consumers Association et al v. Sanderson Farms, Inc., No. 3:17-cv-03592-RS (N.D. Cal. June 22, 2017) Dkt. No. 1 at ¶ 2. The consumer watchdogs alleged that these chemicals are “not natural.” Id. at ¶ 5. Moreover, the alleged presence of the chemicals in Sanderson’s chicken meat “strongly indicate[s] that the birds are raised in intensive-confinement, agro-industrial conditions where cruelty is inherent,” which runs counter to consumer expectations that “All Natural” includes the concept that the chickens are “humanely raised.” Id. at ¶ 71.

Plaintiffs did not simply file a lawsuit, however. They launched a public opinion campaign against Sanderson. This effort included approaching large commercial purchasers of Sanderson’ poultry (Darden Restaurants, Olive Garden) to educate them concerning the company’s alleged practices in an effort to dissuade them from purchasing chicken raised with antibiotics.

Sanderson struck back with a motion to dismiss asserting that Plaintiffs lacked standing and their complaint was pre-empted by the Poultry Products Inspection Act (“PPIA”) and Federal Meat Inspection Act (“FMIA”). Dkt. No. 23 (August 2, 2017); Dkt. No. 32 (September 13, 2017). On February 9, 2018, the district court denied the motion. It dispatched with Sanderson’s standing argument, holding that the diversion of Plaintiffs’ resources from their core public interest mission [i.e., to protect consumers’ right to safe, pollutant free food] to combating the alleged misrepresentations by Sanderson was sufficient injury to confer organizational standing. Dkt. No. 48 at 6 – 7. On pre-emption, the court ruled that there was no express pre-emption and implied pre-emption was not mandated because “[a]llowing plaintiffs to proceed with their advertising claims in no way undermines the PPIA’s [and FMIA’s] objectives of ensuring that poultry products are ‘wholesome, not adulterated, and properly marked, labeled, and packaged.’” Id. at 9. When Sanderson pointed out that the “100% Natural” wording on its label was specifically approved by USDA (as is true with the labels for all meat, poultry, and fish in the U.S.), the court responded that “common sense suggests even ‘language that is technically and scientifically accurate on a label can be manipulated in an advertisement to create a message that is false and misleading to the consumer.’” Id.

It’s at this point that things got nasty. A quick bit of background: the Plaintiff non-profits obtained the testing data upon which they based their complaint from USDA via multiple Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) requests. According to the complaint, the test data revealed that FSIS conducted 69 inspections of Sanderson’s products in 2015-2016, and in 49 cases residue of synthetic drugs, antibiotics (including antibiotics for human use), and pesticides were found. Dkt. No. 1 at ¶ 2. The chemicals in some of the poultry tested were revelatory; for example, Ketamine – a Schedule III anesthetic used legally to induce a trance-like state at the beginning of general anesthesia and illegally (as “Special K,” “Cat Valium,” and “Jet”) as an hallucinogenic and date rape drug. There is, of course, no sane reason for poultry producers to slip Special K into their chickens’ water troughs. Plaintiffs produced this FSIS test results to Sanderson at the time they filed their successful opposition to the Company’s motion to dismiss. According to Sanderson, the results showed negative levels of residue for some 40 chemicals tested – an obvious impossibility. As for chemicals with positive test results, the levels were below the FSIS’s detection limits or Minimum Levels of Applicability (“MLA”). For example, at least some poultry tested positive for Ketoprofen (an NSAID) – but at a level (less than one part per billion) far below the minimum levels of detection established by USDA in its own testing protocol —20 parts per billion (for poultry kidney screening) or 5 parts per billion (for muscle screening). Dkt. No. 49 at 8.

Sanderson was surprised that the FSIS test results were the basis of Plaintiffs’ allegations because “Sanderson has consistently passed FSIS residue testing, which has shown no antibiotic residue or other contaminants in its chicken products, including on the very test dates and locations identified by Plaintiffs in their Complaint.” Dkt. No. 49 at 12. Sanderson’s surprise turned to apoplexy when it discovered that Plaintiffs communicated extensively with USDA and FSIS regarding the test results prior to filing the complaint and were told by the agency that the test results did not reflect the presence of the identified chemicals, but were “preliminary screening data” that had not been confirmed. Id. at 5.

Based on these facts, Sanderson filed a motion for Rule 11 sanctions against Plaintiffs stating that “[t]he problem with Plaintiffs’ storyline is that [its] allegations are entirely false—and Plaintiffs and their attorneys know it.” Id. at 5. In a rare move, USDA’s Office of General Counsel approved Sanderson submitting the declarations of two FSIS officials, Dr. J. Emilio Esteban, Executive Associate for Laboratory Services, and Mark R. Brook, a Government Information Specialist for FSIS, in support of Sanderson’s sanctions motion. Dr. Esteban’s declaration stated that in a teleconference with Plaintiffs’ attorneys, he explained that, in addition to the test results being “preliminary screening data,” “all of the findings in the screening tests . . . were ultimately confirmed as ‘non-detected.’” Dkt. No. 49, Ex. 1. Mr. Brooks swore in his declaration that, upon learning of the filing of the complaint, he spoke with a deputy director at FSIS who participated in conference calls with Plaintiffs and she opined that Plaintiffs’ “seemingly intentionally ignored the explanations of the FOIA data that the USDA/FSIS scientists had provided on the recent conference calls.” Dkt. No. 49, Ex. 2.

Plaintiffs’ opposition to the sanctions motion spends a significant portion of its page limit suggesting some sort of “undue influence” by Sanderson Farms over USDA. (“Sanderson has admitted to contacting USDA in autumn 2017, and perplexing events began to occur around the same time.”) Dkt. No. 55 at 6 – 7. That argument (if it is an argument) is likely to go nowhere. On the merits, Plaintiffs argue that Sanderson “conflat[es] regulatory standards with scientific standards” (which is a bit frightening, if one thinks about it). Id. at 13 – 14. Relatedly, Plaintiffs contend that the issue of the interpretation of the data it received from FSIS is a question for experts — not one to be resolved by the district court on a motion for sanctions. Id. at 15 – 16. Finally, Plaintiffs assert that Sanderson’s admitted use of antibiotics belies any notion that its poultry is “100% Natural” and suggests that its chickens “are not raised as portrayed in Sanderson advertising and referenced in the [complaint].” Id. at 16.

What is it about the living conditions that Plaintiffs argue runs contrary to Sanderson’s USDA approved “100% Natural” label? For Sanderson’s answer, one can consult Bob and Dale, the Sanderson spokesmen in their “The Truth About Chicken” advertising campaign”. What Bob and Dale want you to know is that FDA has never approved the use of steroids or hormones in chickens and USDA does not allow poultry meat to be sold if it is not clear of antibiotics. Therefore, any company that labels its poultry products as “hormone free” or “antibiotic free” in the United States is akin to Ford advertising that its cars and trucks have wheels. It’s a redundancy. While Plaintiffs argue that these advertisements are false and misleading — and assuming that Sanderson and the FSIS officials who submitted declarations are correct that the company’s poultry meat does not contain the chemicals alleged in the complaint — the case seems to boil down to the claim that, for a chicken to be “100% Natural,” a veterinarian can never have administered antibiotics to it (irrespective of whether the antibiotics are present at the time of sale).

The hearing on Sanderson’s motion for sanctions is set for April 5, 2018. Rule 11 motions are notoriously difficult to win. But in this case, Plaintiffs will be arguing that not only should the USDA’s approval of the Company’s “100% Natural” label be disregarded (as the court has already determined), but the USDA’s interpretation of its own test data as well. It will be interesting to see if USDA has anything further to say on those issues.

2018: Food Litigation Trends – Diet Claims

** Part I in our Series on the New Year of Food Litigation **

By: Brent E. Johnson

“Diet” advertising claims are a potential new target of consumer class actions that companies should be on the lookout for in 2018. A trio of cases filed in late 2017 against three of the largest “diet” branded beverage companies — The Coca-Cola Co., Pepsi-Cola Co. and Dr Pepper Snapple Group Inc. — highlight the risk. The complaints in these cases accuse the soda companies of violating the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, which prohibits the labeling of food that is “false or misleading in any particular.” 21 U.S.C. § 343(a). The cases were all filed in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York: Excevarria v. Dr Pepper Snapple Group Inc. et al., 1:17-cv-07957 (S.D.N.Y, Oct. 16, 2017); Geffner. v. The Coca-Cola Co., 1:17-cv-07952 (S.D.N.Y, Oct. 16, 2017); and Manuel v. Pepsi-Cola Co., 1:17-cv-07955 (S.D.N.Y, Oct. 16, 2017).

Plaintiffs claim that inherent in “diet” branding is a promise that the product will assist with weight loss. The complaints allege that this promise is unfulfilled with diet sodas because the artificial sweeteners used in the defendants’ products cause weight gain, not weight loss.

The science referenced in the complaints (while still developing) is intriguing. We all know that reducing caloric intake is one of the foundations of weight loss. Starting in the 1960’s, beverage makers removed natural sugars (high in calories) from products, replacing them with newly discovered “low calorie” sweeteners such as aspartame and sucralose. These sweeteners have been rigorously tested and are generally regarded as safe by FDA. See 46 FR 38283, 48 FR 31376; see also Chobani, LLC v. Dannon Co., Inc., 157 F. Supp. 3d 190 (N.D.N.Y. 2016). More recently, though, these sweeteners have been tested for their efficacy in weight loss. In particular, a recent Yale study suggests that the caloric value of artificial sweeteners is immaterial – it is the sweetness of the products that matters. According to the study, a sweetness “mismatch” – where an intensely sweet product does not have the expected caloric load — causes the body to shut down metabolism. This lower metabolism in many cases causes weight gain.

But what does that mean for “diet” products containing artificial sweeteners? Is the simple use of the term “diet” (particularly where it is only in the brand name, i.e., Diet Coke, or Diet Pepsi) an affirmative representation that the soda is a weight-loss product? As with any false advertising lawsuit, “context is crucial.” Fink v. Time Warner Cable, 714 F.3d 739 (2d Cir. 2013). Is Diet Coke actually sold as a weight loss supplement? Does any reasonable consumer believe that soda (sugar free or not) will make them lose weight? Is “diet” in these contexts a relative term – i.e., as compared to a regular soda. And is “diet” (or similar terms such as “lite” or “low-cal”) too ambiguous and idiosyncratic to attach an absolute meaning as plaintiffs attempt to in these lawsuits? Is it the equivalent of suing McDonald’s because the Happy Meal does not actually make you “happy”?

The diet soda giants have one significant advantage in this debate. The use of the term “diet” in the brand name of soft drinks is grandfathered under the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990 (“NLEA”). Under the NLEA, the word “diet” is specifically approved as a brand name for a soda on the market in 1989 as long as the soda is under 40 calories per serving. 21 U.S.C. § 343(r)(2)(D) (requiring compliance with 21 C.F.R. § 105.66). And the NLEA does not mandate that the use of the word “diet” meet some “weight loss” requirement. FDA is otherwise silent, except for noting that “diet” branding must not be otherwise false and misleading. 21 C.F.R. § 101.13(q)(2). Arguably, the express grandfathering under the NLEA preempts or otherwise forecloses on an accusation that certain sodas cannot properly be branded “diet.”

How courts treat the “diet” claims will be an important issue to watch in 2018. If this concept of artificial-sweetener-as-diet-killer takes hold, it could be a rocky year for foods that make similar claims. We will be watching the “diet” wars with interest . . . and coming in Part II of our multi-part series – xantham gum as the basis of new “natural” class actions.

Supreme Court Skips on Ascertainability

** High Court Won’t Weigh in on Whether “All Natural” Class Requires Ascertainability **

By: Brent E. Johnson

In federal court, Civil Procedure Rule 23 governs the question of whether a class may be certified. The rule specifically identifies four primary requirements for certification: numerosity, commonality, typicality and adequacy. But many courts have added a further requirement – whether the putative class is “ascertainable.” While the question posed by this requirement is phrased differently from court to court, it can be distilled to this: Is there a reasonable and reliable way to identify the members of the proposed class? The Ninth Circuit recently rejected the application of this standard. And, on request for certiorari, the Supreme Court has refused to weigh in on this important issue.

Many federal courts were quick to adopt the ascertainability standard after it found its way into case law, particularly some of the district courts of California, which bear the brunt of the dramatic rise in consumer class actions. See, e.g., Lukovsky v. San Francisco, No. C 05–00389 WHA, 2006 WL 140574, *2 (N.D.Cal. Jan. 17, 2006) (“‘Although there is no explicit requirement concerning the class definition in FRCP 23, courts have held that the class must be adequately defined and clearly ascertainable before a class action may proceed”) (quoting Schwartz v. Upper Deck Co., 183 F.R.D. 672, 679–80 (S.D.Cal.1999)); Thomas & Thomas Rodmakers, Inc. v. Newport Adhesives & Composites, Inc., 209 F.R.D. 159, 163 (C.D.Cal.2002) (“Prior to class certification, plaintiffs must first define an ascertainable and identifiable class. Once an ascertainable and identifiable class has been defined, plaintiffs must show that they meet the four requirements of Rule 23(a), and the two requirements of Rule 23(b)(3)” (citation and footnote omitted)). Generally speaking, a class is sufficiently defined and ascertainable if it is “administratively feasible for the court to determine whether a particular individual is a member.” O’Connor, 184 F.R.D. at 319.

The ascertainability rule appeals to common sense – particularly in consumer class actions. Courts don’t want to certify classes without some reasonable assurance that aggrieved class members will be compensated for the wrong they suffered. Equally important, courts don’t want to create vehicles for petty fraud. As the court observed in Sethavanish v. ZonePerfect Nutrition Co., No. 12–2907–SC, 2014 WL 580696, *56 (N.D.Cal. Feb. 13, 2014), “Plaintiff has yet to present any method for determining class membership, let alone an administratively feasible method. It is unclear how Plaintiff intends to determine who purchased ZonePerfect bars during the proposed class period, or how many ZonePerfect bars each of these putative class members purchased. It is also unclear how Plaintiff intends to weed out inaccurate or fraudulent claims. Without more, the Court cannot find that the proposed class is ascertainable.”

In In re ConAgra Foods, Inc., 90 F. Supp. 3d 919, 969 (C.D. Cal. 2015), consumers brought a putative class action against Con Agra, alleging that the manufacturer deceptively and misleadingly marketed its cooking oils, made from genetically-modified organisms (GMO), as “100% Natural.” A class was certified , inter alia, on the basis that the proposed class was ascertainable. The District Court held that: (i) ascertainability was the law of the Circuit; and (ii) ascertainability was satisfied because membership was governed by a single, objective, criteria – whether an individual purchased the cooking oil during the class period. Id. at 969.

ConAgra, understandably unhappy with the result, appealed the factual basis for the district court’s ascertainability determination. It argued before the Ninth Circuit that plaintiffs did not propose any way to identify class members and could not prove that an administratively feasible method existed for doing so – because, for example, consumers do not generally save grocery receipts and are unlikely to remember details about individual purchases of cooking oil. Briseno v. ConAgra Foods, Inc., 844 F.3d 1121, 1125 (9th Cir. 2017). The Ninth Circuit, however — rather than analyzing whether the plaintiffs satisfied the ascertainability standard — ruled that it has no place in certification proceedings at all. “A separate administrative feasibility prerequisite to class certification is not compatible with the language of Rule 23 . . . Rule 23’s enumerated criteria already address the policy concerns that have motivated some courts to adopt a separate administrative feasibility requirement, and do so without undermining the balance of interests struck by the Supreme Court, Congress, and the other contributors to the Rule.” In short, according to the Ninth Circuit, Rule 23 does not mandate that proposed classes be ascertainable and the lower courts are bound to apply Rule 23 as written.

In so ruling, the Ninth Circuit joined the Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth Circuits. See Sandusky Wellness Ctr., LLC, v. Medtox Sci., Inc., 821 F.3d 992, 995–96 (8th Cir. 2016); Rikos v. Procter & Gamble Co., 799 F.3d 497, 525 (6th Cir. 2015); Mullins v. Direct Digital, LLC, 795 F.3d 654, 658 (7th Cir. 2015), cert. denied, ––– U.S. ––––, 136 S.Ct. 1161, 194 L.Ed.2d 175 (2016). On the opposite side of the ascertainability issue are the Third, Fourth and Eleventh Circuits. Marcus v. BMW of N. Am., LLC, 687 F.3d 583, 593 (3d Cir. 2012); EQT Production Co. v. Adair, 764 F.3d 347, 359 (4th Cir. 2014); Karhu v. Vital Pharm., Inc., — F. App’x —, 2015 WL 3560722 at *3 (11th Cir. June 9, 2015).

ConAgra petitioned the Supreme Court to grant a writ of certiorari on May 10, 2017. It had reason to hope with the Supreme Court recently showing willingness to rule on class action and certification issues. (See prior posts). However, on October 10, 2017, the Supreme Court denied the petition without comment. Conagra Brands, Inc. v. Briseno, No. 16-1221, 2017 WL 1365592 (U.S. Oct. 10, 2017).

With the circuit split still alive, this is not the last we’ll hear on ascertainability. And no doubt defense counsel in affected jurisdictions will find ways to re-shape the reasoning applied in their ascertainability arguments to other parts of the Rule 23 analysis. But, no doubt, with this line of defense gone (for now) in the Ninth Circuit – many more consumer class actions will have their day in California courts.

Is Coconut Oil “Healthy”?

** What are Courts Making of the Plentiful Health Claims Made About Coconut Oil? **

By: Brent E. Johnson

Coconut products are taking an increasingly prominent place in the health food aisles – the shelves are stocked with everything from coconut water to coconut milk to coconut flour. In particular, the last decade has seen the re-emergence of coconut oil (helped by a platoon of celebrity endorsers) as a health food staple. Many marketers have touted coconut oil as a “healthy alternative” to other types of cooking oils. Litigation relating to coconut oil health claims has followed in the last twelve months. The claims made in such lawsuits follow two main themes. First, that coconut oil is inherently unhealthy – and to advertise otherwise is misleading. And second, that health claims made with respect to coconut oil violate specific FDA regulations regarding the term “healthy.”

As to the first claim, it is not particularly controversial that low density lipoproteins (LDL) cholesterol — the so called “bad” cholesterol — contributes to fatty buildup in arteries raising the risk for heart attack, stroke and peripheral artery disease. There also appears to be no question that saturated fats cause the human body to produce excess LDL’s – and that coconut oil is about 90% saturated fat (which is a higher percentage than butter (about 64% saturated fat), beef fat (40%), or even lard (also 40%)). What is unclear is whether all saturated fats are equally “bad” – as some studies suggest that coconut oil’s particular type of saturated fat (medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs)) actually aids in weight loss and helps lower blood cholesterol levels. The science behind these benefits is unsettled.

As to the second question, FDA regulates “nutrient content claim[s].” As we have blogged about in the past, in order to “use the term ‘healthy’ or related words (e.g., ‘health,’ ‘healthful,’ ‘healthfully,’ ‘healthfulness,’ ‘healthier,’ ‘healthiest,’ ‘healthily,’ and ‘healthiness’)” as nutrient content claims, the food must satisfy specific “conditions for fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, and other nutrients.” 21 C.F.R § 101.65(d)(2). Specifically, under 21 C.F.R. § 101.65(d)(2)(i)(F), to make a “healthy” claim, the food must (1) be “’Low fat’ as defined in § 101.62(b)(2),” (2) be “’Low [in] saturated fat’ as defined in § 101.62(c)(2),” and (3) contain “[a]t least 10 percent of the RDI or the DRV per RA of one or more of vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, iron, protein or fiber.” See 21 C.F.R. § 101.65(d)(2)(i)(F). Section 101.62(b)(2)(i)(B) provides the applicable definition of “low fat” for coconut oil products because it has a “Reference Amount Customarily Consumed” (RACC) of less than 30 grams. Under § 101.62(b)(2)(i)(B)’s definition, a food is low fat only if it “contains 3 g or less of fat per reference amount customarily consumed and per 50 g of food.” Under 21 C.F.R. § 101.62(c)(2), a food is “low saturated fat” only if it “contains 1 g or less of saturated fatty acids per (RACC) and not more than 15 percent of calories from saturated fatty acids.” There is very little argument that coconut oil does not meets these metrics. It is not low in fat or low in saturated fat under the FDA’s definitions. But is a general claim of healthfulness on a label a claim about its “nutrient content” – or is it a more generic statement regarding the product overall?

These claims have been made numerous times in recent class actions against coconut oil companies. The facts are not always identical — in some cases the product’s label explicitly states the product is “healthy,” in others the labels use more diffuse terms such that the product is a “superfood” or “nutritious,” and in other cases “healthfulness” is implied by the context of the advertising as a whole. In any case, to date no court has adjudicated the underlying questions raised. The first set of questions revolve around the issue of whether or not coconut oil’s saturated fats are inherently unhealthful? In answering that question, what does “healthy” even mean in the context of cooking oil? Does it mean that there is a complete absence of anything harmful? Does it mean that it is going to make you live longer – or just that it is not going to kill you? Or somewhere in between? Does context play a part here? Would a consumer be cognizant that fats, such as oils, may be healthy in limited ways, but are not if consumed in certain forms or in certain quantities? Is advertising healthy cooking oil different, say, to advertising healthy vitamin supplements? The second unresolved issue is whether claims made on a label about health benefits “nutrition” claims as that term is used in FDA regulations? In Hunter v. Nature’s Way Prod., LLC, No. 16CV532-WQH-BLM, 2016 WL 4262188, at *1 (S.D. Cal. Aug. 12, 2016), the District Court held that these questions could not be definitively answered by defendants on a motion to dismiss and so the case has continued to the class certification stage. The District Court in Jones v. Nutiva, Inc., No. 16-CV-00711-HSG (KAW), 2016 WL 5387760 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 23, 2017), held the same, noting that concepts like “health” and “nutrition” are “difficult to measure concretely” but that the court would not “give the defendant the benefit of the doubt by dismissing the statement as puffery” when the context of the advertising and labeling plays into the analysis of the health claims. This case is also headed towards a certification decision with a motion hearing set for early 2018. Likely, these same questions will raise their heads again on certification briefing, i.e., Is “healthfulness” such an amorphous concept that there is no commonality amongst the class?

In Zemola v. Carrington Tea Co., No. 3:17-cv-00760 (S.D. Cal), defendants have taken a different tact – they have moved for a primary jurisdiction stay of their case based on the pending FDA regulatory proceedings to redefine the term “healthy” in the labeling of food products. As discussed in a prior post, in September 2016, FDA issued a guidance document (Guidance for Industry: Use of the Term “Healthy” in the Labeling of Human Food Products) stating that FDA does not intend to enforce the regulatory requirements for products that use the term healthy if the food is not low in total fat, but has a fat profile makeup of predominantly mono and polyunsaturated fats. FDA also requested public comment on the “Use of the Term “Healthy” in the Labeling of Human Food Products.” Comments were received from consumers and industry stakeholders, reaching 1,100 before the period closed on April 26, 2017. FDA has not provided a timeline as to when revisions to the definition of “healthy” might occur following these public comments. The Zemola Court has yet to rule on the request for a stay.

A number of coconut oil cases have settled. See James Boswell et al. v. Costco Wholesale Corp., No. 8:16-cv-00278 (C.D. Cal) ($775,000 coconut oil settlement based on “healthy” labelling); Christine Cumming v. BetterBody Food & Nutrition LLC, Case No. 37-2016-00019510-CU-BT-CTL (San Diego Sup. Ct) ($1 million settlement).