California

Online Subscriptions Require an Easy Out in California

** New Requirements under California’s Auto Renewal Law Requires Online Cancellation for Online Subscribers **

By: Brent E. Johnson

As we blogged about in the past, in 2010, California’s Automatic Purchase Renewal Statute (“CAPRS”) became effective for businesses offering automatic renewals or continuous service offers to California consumers. See Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 17602. The stated intent of CAPRS is to “end the practice of ongoing charging of consumer credit or debit cards or third party payment accounts without the consumers’ explicit consent for ongoing shipments of a product or ongoing deliveries of service.” Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 17600.

Almost half of US states now have similar laws on the books – some applying to all consumer contracts – others applying only to specific businesses such as gyms or security services. The common denominator amongst these state laws is a requirement to provide disclosure of auto renewal policies in a manner that is clear and conspicuous. See e.g., Connecticut (Conn. Gen. Stat. § 42-126b), Florida (Fla. Stat. § 501.165), Georgia (O.C.G.A. § 13-12-3), Illinois (815 ILCS 601/10), Louisiana (La. Rev. Stat. § 9:2716), Maryland (Md. Code Com. Law § 14-12B-06), New Hampshire (N.H. Rev. Stat. § 358-I:5), New York (N.Y. Gen. Oblig. Law § 5-903), North Carolina (N.C. Gen. Stat. § 75-41), Oregon (Or. Rev. Stat. §§ 646A.293, .295), Rhode Island (R.I. Gen. Laws § 6-13-14), South Carolina (S.C. Code § 44-79-60), South Dakota (S.D. Codified Laws § 49-31-116), Tennessee (Tenn. Code §§ 62-32-325, 47-18-505) and Utah (Utah Code § 15-10-201).

California’s law is among the strictest, requiring explicit consent before charging a consumer’s account for ongoing orders. As a remedy for violation, goods provided to a subscriber on an automatic basis without the required consent are deemed “unconditional gift[s]” (§ 17603) – i.e., “freebies.”

Although not particularly old, California’s law recently received an update– with new provisions going live July 1, 2018. The primary new provision is a requirement that accounts opened online must be permitted to be cancelled online. Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 17602 (c) (“A consumer who accepts an automatic renewal or continuous service offer online shall be allowed to terminate the automatic renewal or continuous service exclusively online.”) No more cumbersome phone calls to customer service agents to cancel accounts. The makeover of California’s law also extends its application to free or discounted trial periods. A cancellation notification must be given prior to the end of this period giving the consumer information on how to cancel prior to being charged the new or non-discounted price. § 17602 (a)(3).

Failure to comply with auto renewals laws has exposed a wide variety of companies to class action complaints (mainly in California under CAPRS). Vemma Nutrition; Spotify; Dropbox; Tinder; LifeLock; Birchbox; Google and Apple have all been sued. Courts are clear that CAPRS does not have an intrinsic private right of action – but that a violation would be an “unlawful” business practice under California’s Unfair Competition Law (UCL) (Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 17200). Johnson v. Pluralsight, LLC, No. 17-15374, 2018 WL 1531067 (9th Cir. Mar. 29, 2018). And as for a remedy under the UCL, failure to honor the “free gift” provision of § 17603 was deemed to be a sufficient allegation to warrant restitution. Id. at * 2.

Companies should take steps to comply with CAPRS and similar laws by:

- Making sure the auto renewal terms are stated clearly and conspicuously – and making sure the terms comprehensively describe the offering, price, frequency of charges and length of minimum terms.

- Having a process to obtain the consumer’s affirmative consent before he or she is charged and providing a mechanism to cancel online, if the subscription is created online.

- Confirming the terms with a notice (such as by email) that includes all relevant offer terms and the cancellation policy prior to the first payment or increase in promotional prices.

California Court Does Not Side With Coffee

** Starbucks and other Coffee Makers Lose Latest Phase of Prop 65 Acrylamide Warning Case **

By: Brent E. Johnson

Background: Acrylamide is a chemical compound first isolated in laboratories in the 1950’s. Since its discovery, it has been used in many industrial applications, such as in the manufacture of polymers, in papermaking, ore processing, oil recovery, and in the manufacture of permanent press fabrics.

Acrylamide was listed by OEHHA as a chemical known to the State of California to cause cancer in 1990 based on studies that showed it produced cancer in laboratory rats and mice. In 2011, it was added to the reproductive and developmental harm list following studies of laboratory animals that showed effects on the growth of offspring exposed in utero as well as genetic damage.

Apart from its industrial uses, in 2002 acrylamide was discovered in foods – in particular starchy, carbohydrate rich plant based foods. The chemical appears to be created when these foods are roasted or fried at temperatures higher than 248 °F – but not in food that had been boiled or steamed. Further, acrylamide levels seem to rise as food is heated for longer periods of time, although researchers are still unsure of the precise mechanisms by which acrylamide is formed. It has been detected irrespective of whether the food is cooked at home, by a restaurant or by commercial food processors and manufacturers. All the good stuff is implicated – french fries, potato chips, other fried and baked snack foods, coffee, roasted nuts, breakfast cereals, crackers, cookies and breads. At present the Prop 65 No Significant Risk Level (NSRL) for acrylamide is 0.2 µg/day. Cal. Code Regs. tit. 27, § 25705 (c)(2).

In 2005, California attorney general Bill Lockyer filed a Prop 65 lawsuit against four makers of French fries and potato chips – H.J. Heinz Co., Frito-Lay, Kettle Foods Inc., and Lance Inc.. People of the State of California v. Frito-Lay, Inc. et al., Case No. BC338956 (Cal. Super. Ct. 2005). The lawsuit was settled in 2008, with the food producers agreeing to reformulate, cutting acrylamide levels to 275 parts per billion (thereby avoiding a Prop 65 warning label). The companies also agreed to pay a combined $3 million in civil penalties.

It was not until 2010 that a private attorney general filed a Prop 65 complaint against the major coffee sellers in California. A number of similar cases were filed and ultimately consolidated in Los Angeles County Superior Court – Council for Education and Research on Toxics v. Starbucks Corp. et al., No. BC435759, and Council for Education and Research on Toxics v. Brad Barry Co. Ltd. et al., No. BC461182. In all, the consolidated litigation involves more than 70 companies including grocery stores, coffee companies, food manufacturers and big-box retailers, such as Whole Foods Market, Trader Joe’s Co., Peet’s Coffee & Tea Inc., Nestle USA Inc., Costco Wholesale Inc. and Wal-Mart Stores.

The first phase of the trial took place in 2014, with a bench trial on several affirmative defenses, including whether acrylamide posed “no significant risk.” Judge Berle ruled in favor of Plaintiff at this phase, rejecting Defendants’ arguments that the level of acrylamide in their coffee products posed no significant risk because a multitude of studies show that coffee consumption does not increase the risk of cancer. The court ruled that the studies assessed the effects of coffee generally, as opposed to the presence of acrylamide in the coffee and were therefore not persuasive. Defendants’ argument that requiring them to post a Prop 65 warning amounted to unconstitutional forced speech was also rejected.

The second phase of the bench trial was held in September of 2017. Several of the defendants settled on the eve of trial, among them were BP, which operates gas stations and convenience stores ($675,000 + warning label); Yum Yum Donuts Inc. ($250,000+ warning label) and 7-Eleven stores ($900,000 + warning label). Starbucks did not settle, although it did begin posting Prop 65 notices in its stores, presumably to limit civil penalties were it unsuccessful at trial.

At the September 2017 trial, Defendants focused their trial strategy on:

- Code Regs. tit. 27, § 25703 (b)(1), which exempts from the normal risk level circumstance where the “chemicals in food are produced by cooking necessary to render the food palatable or to avoid microbiological contamination.” At trial, experts for the defendants testified that there is no commercially viable way to reduce acrylamide in coffee by some other cooking method.

- If § 25703 (b)(1) applies, the statute allows for a higher “alternative risk level” (i.e. not the NSRL of 0.2 µg/day) to apply to chemicals produced in the process of cooking foods if “sound considerations of public health” justify it. As to the appropriate risk level posed by drinking coffee, Defendants’ experts pegged it at up to 19 µg/day of acrylamide in coffee over a lifetime, and otherwise testified that the average person’s exposure to acrylamide in coffee is ten times less. Defendants’ experts also testified that studies found no increased risk of cancer for coffee drinkers, and to the contrary, evidence suggested that moderate coffee consumption is associated with a reduced risk of certain chronic diseases, including certain cancers.

On March 28, 2018, Judge Berle issued a statement of decision under Rule 632 (akin to a preliminary ruling) rejecting the coffee makers’ arguments. Council for Education and Research on Toxics v. Starbucks Corp. et al., No. BC435759 (Cal. Super. Ct. L.A. County March 28, 2018). Judge Berle noted that Prop 65 contemplated an alternative risk level if “public health” justified it. Id. ¶¶ at 75 – 81. But he found that the expert evidence did not persuade him that drinking coffee was strictly speaking a “public health” concern, i.e. that coffee confers a particular benefit to human health. On that basis, the alternative significant risk level defense failed as a threshold matter. Under California procedure, the Defendants can object to these preliminary findings, but it is uncommon for a statement of decision to not ultimately be entered as the judgment. The judge can now set another phase of trial to consider potential civil penalties – up to $2,500 per person exposed each day. In the abstract, that could calculate out to be an astronomical sum, although this preliminary decision may push the parties to the settlement table. We will see who the next target is – acrylamide is after all not just in coffee – but in many cooked and processed foods.

Round Up – Round One

** Monsanto Gets its First Victory in the Battle over Herbicide Prop 65 Listing **

By: Brent E. Johnson

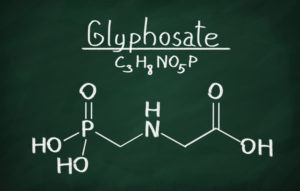

Background: Glyphosate is a molecule that inhibits a biological process only found in plants (not humans and animals). The compound was discovered by a Monsanto chemist in 1970, then patented and brought to market in 1974 as “Round Up.” Initially, the product was only used on a small scale, because, while it is toxic to most weeds, it also kills most crops. However, when Monsanto developed and began introducing genetically modified crops engineered to be resistant to the herbicide (“Roundup Ready” crops), the chemical was able to be used on a broad scale. As a result, the chemical’s use skyrocketed — at the same time that overall herbicide use dropped. In 1987, only 11 million pounds of Round Up were used on U.S. farms – now nearly 300 million pounds are applied each year. A study published in 2015 in the journal Environmental Sciences Europe found that Americans have applied 1.8 million tons of glyphosate since its introduction in 1974. Worldwide, the number is 9.4 million tons. That is enough to spray nearly half a pound of Roundup on every cultivated acre of land in the world. Round Up and Round Up Ready products are worth many billions of dollars.

California’s Office of Environment Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) announced a proposed listing of glyphosate as a Prop 65 chemical on September 4, 2015. The effect of glyphosate’s listing under Prop 65, cannot be underestimated as there are detectable levels of glyphosate in virtually every part of the food chain. Monsanto is famously vigilant in protecting its rights – for example in protecting its crop patents. So when OEHHA proposed the listing, it was inevitable that litigation would follow.

On January 21, 2016, Monsanto struck. It filed a petition in Superior Court in Fresno County seeking injunctive and declaratory relief to enjoin OEHHA from listing glyphosate as a Prop 65 chemical. It did so on the basis of its allegation that the listing mechanism violated the California and United States Constitutions. See Monsanto Co. v. Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, No. 16-CE CG 00183, (Sup. Cal.) That is, primarily, Monsanto complained about how its product came to be added to the list.

Under Cal. Health & Safety Code § 25249.8 (b), which cites to Cal. Lab. Code § 6382 (b)(1), “at a minimum” the Prop 65 list must include those “[s]ubstances listed as human or animal carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).” IARC, based in Lyon, France, is an intergovernmental agency, part of the World Health Organization. In March 2015, IARC issued a report labeling the weed killer glyphosate as a “probable carcinogen.” Glyphosate Monograph, Vol. 112, IARC Monographs Series (IARC, 2015b). That report is not without controversy — for example, the EPA has more recently issued its draft human health risk assessment which concludes that glyphosate is not likely to be carcinogenic to humans. Nevertheless, OEHHA has interpreted § 25249.8 (b) to provide that once IARC lists a chemical, it is mandatory for them to do so also. OEHHA duly noticed its intent to list, prompting the lawsuit.

Monsanto raised four arguments, all ultimately rejected by the trial court.

- First, Monsanto argued that OEHHA unconstitutionally delegated its authority to the IRAC by relying on its assessment that glyphosate is a probable human carcinogen. The doctrine of nondelegation is the rather esoteric theory that one branch of government must not authorize another entity to exercise the power or function that it is constitutionally authorized to exercise, itself. Under California law, this doctrine is not offended if the legislature determines the overarching legislative policy and leaves to others the role of filling in the details. Monsanto Co. v. Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, 2017 WL 3784247 (Cal.Super.) citing Kugler v. Yocum, 69 Cal.2d 371, 375-376 (Cal. 1968). On that point, the court stated that the Prop 65 listing mechanism does not constitute an unconstitutional delegation of authority to an outside agency, since the voters and the Legislature have established the basic legislative scheme and policy and it was permitted to leave the “highly-technical, fact-finding” to the IARC (and other authoritative bodies referred to in the Act).

- Second, the court rejected Monsanto’s due process claims. It held that due processrights are only triggered by judicial or adjudicatory actions. California Gillnetters Assn. v. Department of Fish & Game, 39 Cal.App.4th 1145, 1160 (Cal. 1995). The court stated the Prop 65 listing was not adjudicative, but a “quasi-legislative act.”

- Third, the court rejected Monsanto’s arguments that the listing process violated California’s Article II, Section 12, which prohibits private corporations from holding office or performing legislative functions. It found that there are no facts that would tend to indicate that the IARC is a “private corporation,” or that IARC has an pecuniary interest in being given the power to name certain chemicals on its list of possible carcinogens.

- Fourth, the court gave short shrift to Monsanto’s claim that listing glyphosate would violate its right to free speech under the California and Federal constitutions, in particular the inherent protections for commercial speech from unwarranted governmental regulation. The court held that the First Amendment claim was not ripe for adjudication because the mere listing of glyphosate does not in and of itself require Monsanto to provide a warning and it may never be required to give a warning.

Monsanto appealed this ruling. It also sought a stay of the trial court’s decision pending its appeal, The appellate court and the California Supreme Court rejected these requests for a stay in June 2017. OEHHA wasted no time after the Supreme Court’s decision adding glyphosate to the list on July 7, 2017. After this ruling, subject to the substantive appeal of the trial court decision, July 7, 2018 was to be the date by which companies must comply with the Prop 65 requirements for glyphosate.

Not content to wait idly by, Monsanto moved the battle to Federal Court, On November 15, 2017, it filed a complaint for declaratory and injunctive relief in the Eastern District of California (No. 2:17-cv-02401-WBS-EFB) together with the National Association of Wheat Growers, National Corn Growers Association, United States Durum Growers Association, Western Plant Health Association, Missouri Farm Bureau, Iowa Soybean Association, South Dakota Agri-Business Association, North Dakota Grain Growers Association, Missouri Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Associated Industries of Missouri and the Agribusiness Association of Iowa. So far, the following have also signed on as amicus – the State of Wisconsin, South Dakota, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Michigan, Kansas, Louisiana, Iowa, Indiana, Idaho and Missouri.

The complaint starts by attacking the IARC listing, noting that a dozen other global regulatory and scientific agencies have found no link between glyphosate and cancer. The allegedly “false” warning under Prop 65, plaintiffs argue, compels speech violating Plaintiff’s First Amendment rights. Plaintiffs also argue that the listing and warning requirement conflict with, and are preempted by Federal legislation,notably the United States Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) and Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA). The complaint also raises the issue rejected by the state court that the listing process violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Plaintiffs filed a Motion for Preliminary Injunction on December 6, 2017, which was heard on February 20, 2018. On February 26, 2018, U.S. District Court Judge William B. Shubb ruled in favor of Monsanto and the other named plaintiffs. No. CV 2:17-2401 WBS EFB, 2018 WL 1071168, at *1 (E.D. Cal. Feb. 26, 2018). The order declined to go so far as to remove glyphosate from the Proposition 65 list, but at least for now, bars the State of California from imposing the corresponding warning requirement while the case challenging its listing proceeds on the merits.

The court primarily relied on Monsanto’s First Amendment argument in issuing the injunction. Judge Shubb concluded that, to the extent Prop 65 necessitates warnings for glyphosate, California is in essence compelling commercial speech. The court held that the government may only require commercial speakers to disclose “purely factual and uncontroversial information” about commercial products or services, as long as the “disclosure requirements are reasonably related” to a substantial government interest and are neither “unjustified [n]or unduly burdensome.” Id. at * 5 citing Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel of Supreme Court of Ohio, 471 U.S. 626, 651 (1985); CTIA-The Wireless Ass’n v. City of Berkeley, 854 F.3d 1105, 1118 (9th Cir. 2017).

In this case, the court held that the link between cancer and glyphosate was not uncontroverted – particularly where “only one health organization had found that the substance in question causes cancer and virtually all other government agencies and health organizations that have reviewed studies on the chemical had found there was no evidence that it caused cancer.” Id. at *6. The court went further stating, “[u]nder these facts, the message that glyphosate is known to cause cancer is misleading at best.” Id. Accordingly, it was determined that the balancing of interests involved weighed in favor of restraining the enforcement of the warning requirement for glyphosate while the remainder of the case was decided.

The court enjoined “defendants” (i.e. OEHHA and the California Attorney General) and “their agents and employees, all persons or entities in privity with them, and anyone acting in concert with them.” Id. at *8. We will see if private Prop 65 bounty hunters consider themselves bound by this injunction.

One area the dispute will also move to is the No Significant Risk Levels (NSRLs) for glyphosate. If the NSRL is set at a particularly high level (perhaps based on the factual controversies referred to above), then the issue over listing may be mooted. Again, however, a sky high NSRL still may not dissuade Prop 65 bounty hunters.

Supreme Court Skips on Ascertainability

** High Court Won’t Weigh in on Whether “All Natural” Class Requires Ascertainability **

By: Brent E. Johnson

In federal court, Civil Procedure Rule 23 governs the question of whether a class may be certified. The rule specifically identifies four primary requirements for certification: numerosity, commonality, typicality and adequacy. But many courts have added a further requirement – whether the putative class is “ascertainable.” While the question posed by this requirement is phrased differently from court to court, it can be distilled to this: Is there a reasonable and reliable way to identify the members of the proposed class? The Ninth Circuit recently rejected the application of this standard. And, on request for certiorari, the Supreme Court has refused to weigh in on this important issue.

Many federal courts were quick to adopt the ascertainability standard after it found its way into case law, particularly some of the district courts of California, which bear the brunt of the dramatic rise in consumer class actions. See, e.g., Lukovsky v. San Francisco, No. C 05–00389 WHA, 2006 WL 140574, *2 (N.D.Cal. Jan. 17, 2006) (“‘Although there is no explicit requirement concerning the class definition in FRCP 23, courts have held that the class must be adequately defined and clearly ascertainable before a class action may proceed”) (quoting Schwartz v. Upper Deck Co., 183 F.R.D. 672, 679–80 (S.D.Cal.1999)); Thomas & Thomas Rodmakers, Inc. v. Newport Adhesives & Composites, Inc., 209 F.R.D. 159, 163 (C.D.Cal.2002) (“Prior to class certification, plaintiffs must first define an ascertainable and identifiable class. Once an ascertainable and identifiable class has been defined, plaintiffs must show that they meet the four requirements of Rule 23(a), and the two requirements of Rule 23(b)(3)” (citation and footnote omitted)). Generally speaking, a class is sufficiently defined and ascertainable if it is “administratively feasible for the court to determine whether a particular individual is a member.” O’Connor, 184 F.R.D. at 319.

The ascertainability rule appeals to common sense – particularly in consumer class actions. Courts don’t want to certify classes without some reasonable assurance that aggrieved class members will be compensated for the wrong they suffered. Equally important, courts don’t want to create vehicles for petty fraud. As the court observed in Sethavanish v. ZonePerfect Nutrition Co., No. 12–2907–SC, 2014 WL 580696, *56 (N.D.Cal. Feb. 13, 2014), “Plaintiff has yet to present any method for determining class membership, let alone an administratively feasible method. It is unclear how Plaintiff intends to determine who purchased ZonePerfect bars during the proposed class period, or how many ZonePerfect bars each of these putative class members purchased. It is also unclear how Plaintiff intends to weed out inaccurate or fraudulent claims. Without more, the Court cannot find that the proposed class is ascertainable.”

In In re ConAgra Foods, Inc., 90 F. Supp. 3d 919, 969 (C.D. Cal. 2015), consumers brought a putative class action against Con Agra, alleging that the manufacturer deceptively and misleadingly marketed its cooking oils, made from genetically-modified organisms (GMO), as “100% Natural.” A class was certified , inter alia, on the basis that the proposed class was ascertainable. The District Court held that: (i) ascertainability was the law of the Circuit; and (ii) ascertainability was satisfied because membership was governed by a single, objective, criteria – whether an individual purchased the cooking oil during the class period. Id. at 969.

ConAgra, understandably unhappy with the result, appealed the factual basis for the district court’s ascertainability determination. It argued before the Ninth Circuit that plaintiffs did not propose any way to identify class members and could not prove that an administratively feasible method existed for doing so – because, for example, consumers do not generally save grocery receipts and are unlikely to remember details about individual purchases of cooking oil. Briseno v. ConAgra Foods, Inc., 844 F.3d 1121, 1125 (9th Cir. 2017). The Ninth Circuit, however — rather than analyzing whether the plaintiffs satisfied the ascertainability standard — ruled that it has no place in certification proceedings at all. “A separate administrative feasibility prerequisite to class certification is not compatible with the language of Rule 23 . . . Rule 23’s enumerated criteria already address the policy concerns that have motivated some courts to adopt a separate administrative feasibility requirement, and do so without undermining the balance of interests struck by the Supreme Court, Congress, and the other contributors to the Rule.” In short, according to the Ninth Circuit, Rule 23 does not mandate that proposed classes be ascertainable and the lower courts are bound to apply Rule 23 as written.

In so ruling, the Ninth Circuit joined the Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth Circuits. See Sandusky Wellness Ctr., LLC, v. Medtox Sci., Inc., 821 F.3d 992, 995–96 (8th Cir. 2016); Rikos v. Procter & Gamble Co., 799 F.3d 497, 525 (6th Cir. 2015); Mullins v. Direct Digital, LLC, 795 F.3d 654, 658 (7th Cir. 2015), cert. denied, ––– U.S. ––––, 136 S.Ct. 1161, 194 L.Ed.2d 175 (2016). On the opposite side of the ascertainability issue are the Third, Fourth and Eleventh Circuits. Marcus v. BMW of N. Am., LLC, 687 F.3d 583, 593 (3d Cir. 2012); EQT Production Co. v. Adair, 764 F.3d 347, 359 (4th Cir. 2014); Karhu v. Vital Pharm., Inc., — F. App’x —, 2015 WL 3560722 at *3 (11th Cir. June 9, 2015).

ConAgra petitioned the Supreme Court to grant a writ of certiorari on May 10, 2017. It had reason to hope with the Supreme Court recently showing willingness to rule on class action and certification issues. (See prior posts). However, on October 10, 2017, the Supreme Court denied the petition without comment. Conagra Brands, Inc. v. Briseno, No. 16-1221, 2017 WL 1365592 (U.S. Oct. 10, 2017).

With the circuit split still alive, this is not the last we’ll hear on ascertainability. And no doubt defense counsel in affected jurisdictions will find ways to re-shape the reasoning applied in their ascertainability arguments to other parts of the Rule 23 analysis. But, no doubt, with this line of defense gone (for now) in the Ninth Circuit – many more consumer class actions will have their day in California courts.

Is Coconut Oil “Healthy”?

** What are Courts Making of the Plentiful Health Claims Made About Coconut Oil? **

By: Brent E. Johnson

Coconut products are taking an increasingly prominent place in the health food aisles – the shelves are stocked with everything from coconut water to coconut milk to coconut flour. In particular, the last decade has seen the re-emergence of coconut oil (helped by a platoon of celebrity endorsers) as a health food staple. Many marketers have touted coconut oil as a “healthy alternative” to other types of cooking oils. Litigation relating to coconut oil health claims has followed in the last twelve months. The claims made in such lawsuits follow two main themes. First, that coconut oil is inherently unhealthy – and to advertise otherwise is misleading. And second, that health claims made with respect to coconut oil violate specific FDA regulations regarding the term “healthy.”

As to the first claim, it is not particularly controversial that low density lipoproteins (LDL) cholesterol — the so called “bad” cholesterol — contributes to fatty buildup in arteries raising the risk for heart attack, stroke and peripheral artery disease. There also appears to be no question that saturated fats cause the human body to produce excess LDL’s – and that coconut oil is about 90% saturated fat (which is a higher percentage than butter (about 64% saturated fat), beef fat (40%), or even lard (also 40%)). What is unclear is whether all saturated fats are equally “bad” – as some studies suggest that coconut oil’s particular type of saturated fat (medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs)) actually aids in weight loss and helps lower blood cholesterol levels. The science behind these benefits is unsettled.

As to the second question, FDA regulates “nutrient content claim[s].” As we have blogged about in the past, in order to “use the term ‘healthy’ or related words (e.g., ‘health,’ ‘healthful,’ ‘healthfully,’ ‘healthfulness,’ ‘healthier,’ ‘healthiest,’ ‘healthily,’ and ‘healthiness’)” as nutrient content claims, the food must satisfy specific “conditions for fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, and other nutrients.” 21 C.F.R § 101.65(d)(2). Specifically, under 21 C.F.R. § 101.65(d)(2)(i)(F), to make a “healthy” claim, the food must (1) be “’Low fat’ as defined in § 101.62(b)(2),” (2) be “’Low [in] saturated fat’ as defined in § 101.62(c)(2),” and (3) contain “[a]t least 10 percent of the RDI or the DRV per RA of one or more of vitamin A, vitamin C, calcium, iron, protein or fiber.” See 21 C.F.R. § 101.65(d)(2)(i)(F). Section 101.62(b)(2)(i)(B) provides the applicable definition of “low fat” for coconut oil products because it has a “Reference Amount Customarily Consumed” (RACC) of less than 30 grams. Under § 101.62(b)(2)(i)(B)’s definition, a food is low fat only if it “contains 3 g or less of fat per reference amount customarily consumed and per 50 g of food.” Under 21 C.F.R. § 101.62(c)(2), a food is “low saturated fat” only if it “contains 1 g or less of saturated fatty acids per (RACC) and not more than 15 percent of calories from saturated fatty acids.” There is very little argument that coconut oil does not meets these metrics. It is not low in fat or low in saturated fat under the FDA’s definitions. But is a general claim of healthfulness on a label a claim about its “nutrient content” – or is it a more generic statement regarding the product overall?

These claims have been made numerous times in recent class actions against coconut oil companies. The facts are not always identical — in some cases the product’s label explicitly states the product is “healthy,” in others the labels use more diffuse terms such that the product is a “superfood” or “nutritious,” and in other cases “healthfulness” is implied by the context of the advertising as a whole. In any case, to date no court has adjudicated the underlying questions raised. The first set of questions revolve around the issue of whether or not coconut oil’s saturated fats are inherently unhealthful? In answering that question, what does “healthy” even mean in the context of cooking oil? Does it mean that there is a complete absence of anything harmful? Does it mean that it is going to make you live longer – or just that it is not going to kill you? Or somewhere in between? Does context play a part here? Would a consumer be cognizant that fats, such as oils, may be healthy in limited ways, but are not if consumed in certain forms or in certain quantities? Is advertising healthy cooking oil different, say, to advertising healthy vitamin supplements? The second unresolved issue is whether claims made on a label about health benefits “nutrition” claims as that term is used in FDA regulations? In Hunter v. Nature’s Way Prod., LLC, No. 16CV532-WQH-BLM, 2016 WL 4262188, at *1 (S.D. Cal. Aug. 12, 2016), the District Court held that these questions could not be definitively answered by defendants on a motion to dismiss and so the case has continued to the class certification stage. The District Court in Jones v. Nutiva, Inc., No. 16-CV-00711-HSG (KAW), 2016 WL 5387760 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 23, 2017), held the same, noting that concepts like “health” and “nutrition” are “difficult to measure concretely” but that the court would not “give the defendant the benefit of the doubt by dismissing the statement as puffery” when the context of the advertising and labeling plays into the analysis of the health claims. This case is also headed towards a certification decision with a motion hearing set for early 2018. Likely, these same questions will raise their heads again on certification briefing, i.e., Is “healthfulness” such an amorphous concept that there is no commonality amongst the class?

In Zemola v. Carrington Tea Co., No. 3:17-cv-00760 (S.D. Cal), defendants have taken a different tact – they have moved for a primary jurisdiction stay of their case based on the pending FDA regulatory proceedings to redefine the term “healthy” in the labeling of food products. As discussed in a prior post, in September 2016, FDA issued a guidance document (Guidance for Industry: Use of the Term “Healthy” in the Labeling of Human Food Products) stating that FDA does not intend to enforce the regulatory requirements for products that use the term healthy if the food is not low in total fat, but has a fat profile makeup of predominantly mono and polyunsaturated fats. FDA also requested public comment on the “Use of the Term “Healthy” in the Labeling of Human Food Products.” Comments were received from consumers and industry stakeholders, reaching 1,100 before the period closed on April 26, 2017. FDA has not provided a timeline as to when revisions to the definition of “healthy” might occur following these public comments. The Zemola Court has yet to rule on the request for a stay.

A number of coconut oil cases have settled. See James Boswell et al. v. Costco Wholesale Corp., No. 8:16-cv-00278 (C.D. Cal) ($775,000 coconut oil settlement based on “healthy” labelling); Christine Cumming v. BetterBody Food & Nutrition LLC, Case No. 37-2016-00019510-CU-BT-CTL (San Diego Sup. Ct) ($1 million settlement).

No Love from FDA

**FDA Warns Bakery it Cannot Label “Love” As An Ingredient **

By: Brent E. Johnson

A warning letter published by the Food & Drug Administration and issued to Massachusetts-based Nashoba Brook Bakery highlights that FDA has little tolerance for eccentricity when it comes to labelling compliance. According to the letter, Nashoba sold granola with labeling that said that one of the ingredients was “love.” Charming as that may be, FDA was not impressed, writing that “Ingredients required to be declared on the label or labeling of food must be listed by their common or usual name . . . ‘Love’ is not a common or usual name of an ingredient, and is considered to be intervening material because it is not part of the common or usual name of the ingredient.” It is not clear whether FDA was inspired by 2016 research that found that study participants rated identical food as superior in taste and flavor if they were told it was lovingly prepared using a family-favorite recipe. We’ll see if there are any repercussions to the bakery from the FDA Love Letter – other than the free publicity it garnered.

For those who follow our blog, you’ll recall we have written in the past about KIND®, who was also on the receiving end of a not so kind letter asking the company to remove any mention of “healthy” from its packaging and website. Notably, later in 2016, the FDA had a change of heart – on April 22, 2016 emailing Kind informing the company that it could return to its “healthy” language – as long as the use of “healthy” is in relation to its “corporate philosophy,” and not a “nutrient claim” (the latter being the statutory predicate under 21 C.F.R. § 101.65). Unfortunately for Kind, the 2015 letter prompted a suite of lawsuits. A number were filed in California: Kaufer v. Kind LLC., No. 2:15-cv-02878 (C.D. Cal), Galvez v. Kind LLC., No. 2:15-cv-03082 (C.D. Cal); Illinois and New York: Cavanagh v. Kind, LLC., 1:15-cv-03699-WHP (S.D.N.Y.), Short et al v. Kind LLC, 1:15-cv-02214 (E.D.N.Y). Ultimately, a multi-district panel assigned the case to the Southern District of New York (In Re: Kind LLC “Healthy” and “All Natural” Litigation, 1:15-md-02645-WHP). The cases in large part were voluntarily withdrawn after FDA sent its April 22, 2016 “change of heart” email.

That said, plaintiffs in the MDL case also made claims that Kind Bars are not “All Natural.” The Court stayed the “All Natural” component of the action pending FDA’s consideration of the term under the primary jurisdiction doctrine. Dkt. No. 83 (see also our previous post on primary jurisdiction “all natural cases.”) Plaintiffs have recently sought to lift the stay, arguing that FDA is taking too long. Dkt. No. 109. Plaintiffs have also amended their “All Natural” claims to encompass the additional question of whether Kind’s “Non-GMO” statements comport with state GMO laws. Kind responded by arguing that such state law claims are preempted by the National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard, Pub. L. 114-216 (“National GMO Standard”) (7 U.S.C. § 1639i). Dkt. No. 101. The Court has heard oral argument on the GMO preemption issue and the lifting of the stay, but is yet to rule on either.

Splitting Hairs Over Milk

** Class Actions Dismissed (and Stayed) on Question of Who Can Call Their Product Milk **

By: Brent E. Johnson

As anyone who has watched “Meet the Parents” knows, “milk” has traditionally been applied to mammalian products. Recently, however, the term has been expanded to describe a wide range of non-dairy products such as liquids partially derived from almonds, oats, soy, rice, and cashews. Can these products rightly be called “milk”? Plaintiffs’ attorneys in California have decided to put that question to the test. In Kelley v. WWF Operating Co., No. 1:17-CV-117-LJO-BAM, (E.D. Cal), plaintiffs based their suit on Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations dealing with “imitation” foods – defined by FDA as a food which “act[s] . . . [a]s a substitute for and resembles another food but is nutritionally inferior to that food.” 21 C.F.R. § 101.3 (e)(1). Under these regulations, an imitation food must be clearly labelled (in a type of uniform size and prominence to the name of the food imitated) with the word “imitation.” 21 C.F.R. § 101.3 (e). Otherwise, the product is “misbranded” under section 403(c) of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. In Kelly, plaintiffs alleged that WWF’s Silk Almond Milk beverages should have been labelled with the “imitation” nomenclature because they are not “milk” and (in some respects) are nutritionally inferior.

Defendant responded with a motion to dismiss, arguing that no reasonable customer would be misled by the use of the term “almond milk” on its products because the consuming public knows exactly what it is getting – what Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines as “a food product produced from seeds or fruit that resembles and is used similarly to cow’s milk.”

The Kelly case follows a broader, and as yet unresolved, public debate on this definition. Indeed, there’s a war over the definition of milk. Both the House and Senate are currently contemplating versions of the Defending Against Imitations and Replacements of Yogurt, Milk and Cheese to Promote Regular Intake of Dairy Everyday (DAIRY PRIDE) Act (H.R.778 House Version) (S.130 Senate Version). The bills are sponsored by senators and congressmen from dairy rich states (Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) and Rep. Peter Welch (D-VT)). The House bill included five original co-sponsors: Rep. Michael Simpson (R-ID); Rep. Sean Duffy (R-WI); Rep. Joe Courtney (D-CT); Rep. David Valadao (R-CA); and Rep. Suzan DelBene (D-WA). If enacted, the bills would amend the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to prohibit the sale of any food using the market name of a dairy product that is not the milk of a hooved animal, is not derived from such milk or does not contain such milk as a primary ingredient. As supporters of the bills have observed (summed up by a quote from the Holstein Association USA): “After milking animals for 40 years I’ve never been able to milk an almond.”

FDA has not stepped into the fray even though it has been petitioned to do so. In March 2017, FDA received a Citizen Petition from the Good Food Institute requesting it promulgate “regulations clarifying how foods may be named by reference to the names of other foods” and specifically requesting, among other things, that FDA issue regulations that would permit plant-based beverages to be called “milk.” On the other side, the National Milk Producers Federation (NMPF) wrote in a letter addressed to the FDA and sent on August 29th that the application of dairy-related terms like “milk” to market plant-based beverages creates consumer confusion in the marketplace.

In Kelly, the Court was not troubled by FDA’s inaction. It found that, because FDA was “poised” to consider the question raised by this suit (although it has never said as much), it was “on their radar,” and therefore FDA should have the opportunity to decide the question, itself. Under the Primary Jurisdiction Doctrine – which we have blogged about in the past – the Court stayed the matter indefinitely. Kelley v. WWF Operating Co., No. 1:17-CV-117-LJO-BAM, 2017 WL 2445836, at *6 (E.D. Cal. June 6, 2017).

In a similar case filed against Blue Diamond in California state court but transferred to the U.S. District Court for the Central District, the defendant was successful on its motion to dismiss. Painter v. Blue Diamond Growers, No. 1:17-CV-02235-SVW-AJW, (C.D. Cal. May 24, 2017). In that case, Judge Wilson held that it was completely implausible that there was consumer confusion. Judge Wilson held that “Almond milk” accurately describes defendant’s product. See Ang v. Whitewave Foods Co., No. 13-CV-1953, 2013 WL 6492353, at *3 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 10, 2013) (finding as a matter of law that no reasonable consumer would confuse soymilk or almond milk for dairy milk); Gilson v. Trader Joe’s Co., No. 13-CV-01333-WHO, 2013 WL 5513711, at *7 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 4, 20 13) (finding at the pleading stage that no reasonable consumer would believe that a product labeled Organic Soy Milk, including the explicit statement that it is “LACTOSE & DAIRY FREE”, has the same qualities as cow’s milk). Quoting from the Ang court, Judge Wilson reasoned that a reasonable consumer knows veggie bacon does not contain pork, that flourless chocolate cake does not contain flour, and that e-books are not made out of paper. Judge Wilson also held that plaintiff’s case would create a de facto labelling standard using state law that was stricter than the FDCA requirement and, therefore the case was preempted. See also Gilson v. Trader Joe’s Co., No. 13-CV-01333-VC, 2015 WL 9121232, at *2 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 1, 20 15) (finding state law claims against the use of the term “soymilk” preempted by the FDCA).

Plaintiffs in the Painter case have appealed to the Ninth Circuit. Painter v. Blue Diamond Growers, No. 17-55901 (9th. Cir. June 26, 2017). We’ll keep you updated on the progress of the case.

FYI on ECJ

** In the Wake of FDA’s Guidance, Evaporated Cane Juice Cases Continue . . . . **

By: Brent E. Johnson

As we have blogged about in the past the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued guidance in 2016 that it is false or misleading to describe sweeteners made from sugar cane as “evaporated cane juice” (ECJ). Guidance for Industry: Ingredients Declared as Evaporated Cane Juice.

It is common knowledge that cane sugar is made by processing sugar cane – crushing the cane to extract the juice, evaporating that juice, and crystalizing the syrup that remains. To make white sugar, the crystals undergo additional crystallization to strip out molasses. The primary difference between standard white sugar and the product known as ECJ is that the latter skips the second crystallization process. ECJ is sold as a standalone product (e.g., in health food stores) and since the early 2000’s has been introduced as a white sugar substitute in products such as yogurt and lemonade.

The plaintiffs’ bar alleges that ECJ is identical to refined sugar from a nutrient and caloric standpoint and, therefore, food labelling using the term ECJ misleads health-conscious consumers into thinking it is a better sweetener option (or not sugar at all). Defendants respond that ECJ is precisely what it says — the evaporated juice from the cane of the sugar plant — and is therefore a wholly accurate term to describe a type of sweetener that is made from sugar cane but undergoes less processing than white sugar. See e.g., Morgan v Wallaby Yogurt Company, No. CV 13-0296-CW, 2013 WL 11231160 (N.D. Cal, April 8, 2013) (Mot. to Dismiss).

FDA regulations are implicated in this controversy because they prohibit the use of an ingredient name that is not the “common or usual name” of the food. 21 CFR 101.3 (b) & (d). The common or usual name of a food or ingredient can be established by common usage or by regulation. In the case of “sugar,” FDA regulations establish that sucrose obtained by crystallizing sugar cane or sugar beet juice that has been extracted by pressing or diffusion, then clarified and evaporated, is commonly and usually called “sugar.” 21 CFR 101.4(b)(20). The question for the FDA in 2016 when it was considering its ECJ Guidelines, therefore, was whether ECJ fits under this definition and therefore should be identified by the common or usual name – sugar. This question was complicated by FDA’s heavy regulation of the term “juice,” which is also defined in the federal register. 21 CFR 101.30.

On October 7, 2009, FDA first stepped into the ECJ fray, publishing a draft guidance entitled “Guidance for Industry: Ingredients Declared as Evaporated Cane Juice” (74 FR 51610) to advise the relevant industries of FDA’s view that sweeteners derived from sugar cane syrup should not be declared on food labels as “evaporated cane juice” because that term falsely suggests the sweetener is akin to fruit juice. On March 5, 2014, FDA reopened the comment period for the draft guidance seeking further comments, data, and information (79 FR 12507). On May 25, 2016, FDA updated this guidance (81 FR 33538), superseding the 2009 version, but not changing its position that it is false or misleading to describe sweeteners made from sugar cane as ECJ. FDA reasoned that the term “cane juice”— as opposed to cane syrup or cane sugar—calls to mind vegetable or fruit juice, see 21 CFR 120.1(a), which the FDA said is misleading as sugar cane is not typically eaten as a fruit or vegetable. As such, the FDA concluded that the term “evaporated cane juice” fails to disclose that the ingredient’s “basic nature” is sugar. 2016 Guidance, Section III. As support, FDA cited the Codex Alimentarius Commission — a source for international food standards sponsored by the World Health Organization and the United Nations. FDA therefore advised that “‘evaporated cane juice’ is not the common name of any type of sweetener and should be declared on food labels as ‘sugar,’ preceded by one or more truthful, non-misleading descriptors if the manufacturer so chooses.” 2016 Guidance, Section III.

Bear in mind that FDA guidance is not binding on courts and, in and of itself, does not create a private right of action. 21 U.S.C. § 337(a) (“[A]ll such proceedings for the enforcement, or to restrain violations, of [the FDCA] shall be by and in the name of the United States”); see POM Wonderful LLC v. Coca-Cola Co., 573 U.S. ___ (2014); Buckman Co. v. Pls.’ Legal Comm., 531 U.S. 341, 349 n.4 (2001); Turek v. Gen. Mills, Inc., 662 F.3d 423, 426 (7th Cir. 2011); see also Smith v. U.S. Dep’t of Agric., 888 F. Supp. 2d 945, 955 (S.D. Iowa 2012) (holding that there is no private right of action under USDA statute). In false advertising cases, the governing test is what consumers, themselves, think – not what FDA thinks. For example, in Mason v. Coca-Cola Co., plaintiffs alleged that “Diet Coke Plus” was misleading because the word “Plus” implied the product was “healthy” under FDA regulations. 774 F. Supp. 2d 699 (D.N.J. 2011). The court begged to differ: “At its core, the complaint is an attempt to capitalize on an apparent and somewhat arcane violation of FDA food labeling regulations . . . not every regulatory violation amounts to an act of consumer fraud . . . . It is simply not plausible that consumers would be aware of [the] FDA regulations [plaintiff relies on].” Id. at 705 n.4; see also Polk v. KV Pharm. Co., No. 4:09-CV-00588 SNLJ, 2011 WL 6257466, at *7 (E.D. Mo. Dec. 15, 2011); In re Frito-Lay N. Am., Inc. All Natural Litig., No. 12-MD-2413 RRM RLM, 2013 WL 4647512, at *15 (E.D.N.Y. Aug. 29, 2013) (“[T]he Court [cannot] conclude that a reasonable consumer, or any consumer, is aware of and understands the various federal agencies’ views on the term natural.”) That said, while FDA’s guidance is not alone dispositive – it certainly lends weight to the question of what a consumer’s state of mind would be with respect to the question of false and misleading labelling.

In the interim between FDA opening up public comment in 2014 on the ECJ question and its release of the 2016 guidance, many cases on this issue were stayed awaiting the outcome of FDA’s deliberations (based on the primary jurisdiction doctrine). Saubers v. Kashi Co., 39 F. Supp. 3d 1108 (S.D. Cal. 2014) (primary jurisdiction invoked with respect to “evaporated cane juice” labels) (collecting cases) see, e.g., Gitson, et al. v. Clover-Stornetta Farms, Inc., Case No. 3:13-cv-01517-EDL (N.D. Cal. Jan. 7, 2016); Swearingen v. Amazon Preservation Partners, Inc., Case No. 13-cv-04402-WHO (N.D. Cal. Jan. 11, 2016). With that guidance published, the stayed suits are now set to proceed. And, as to be expected, many new cases have been filed over ECJ labeling. Notably, complaints have been filed far away from the traditional “food court” in the Northern District of California. For example, more than a dozen ECJ cases have recently been filed in St. Louis – the targeted defendants include manufacturers of Pacqui Corn Chips (Dominique Morrison v. Amplify Snack Brands Inc., No. 4:17-cv-00816-RWS (E.D. Mo.) and Bakery on Main Granola (Callanan v. Garden of Light, Inc., No. 4:17-cv-01377 (E.D. Mo.)

Where are courts landing on the ECJ question?

In Swearingen v. Santa Cruz Natural, Inc., No. 13-cv-04291 (N.D. Cal.), a complaint was filed on September 16, 2013, stating that plaintiffs were health-conscious consumers who wish to avoid “added sugars” and who, after noting that “sugar” was not listed as an ingredient, were misled when they purchased Santa Cruz Lemonade Soda, Orange Mango Soda, Raspberry Lemonade Soda, and Ginger Ale Soda which contained ECJ. On July 1, 2014, the matter was stayed by Judge Illston pursuant to the primary jurisdiction doctrine. The stay was lifted in June 2016 following a status conference noting the FDA’s final guidance on ECJ – and thereafter supplemental briefing on Santa Cruz’s motion to dismiss was considered. The Court issued its order on August 17, 2016 (2016 WL 4382544), refusing to dismiss under Rule 12, noting the following:

- Products not purchased. Santa Cruz argued that plaintiffs had not claimed to have personally purchased every single beverage referred to in the complaint and therefore lacked standing as to those products. Judge Illston, however, sided with those courts that have concluded that an actual purchase is not required to establish injury-in-fact under Article III, but rather, that when “plaintiffs seek to proceed as representatives of a class . . . ‘the critical inquiry seems to be whether there is sufficient similarity between the products purchased and not purchased.” 2016 WL 4382544 at *8 (quoting Astiana v. Dreyer’s Grand Ice Cream, Inc., 2012 WL 2990766, at *11 (N.D. Cal. July 20, 2012). Because all of the fruit beverages at issue were of the same type of food product, Judge Illston concluded the plaintiffs had standing for all of them.

- Ingredient Lists. Santa Cruz also argued that plaintiffs could not meet the “reasonable consumer” test of the California consumer protection statutes because it was implausible that a consumer would read the mandatory Nutrition Facts label immediately adjacent to the impugned ingredient list – which clearly identified the product as having 29 grams of sugar — and conclude that it did not contain added sugar. Judge Illston noted that she had “some reservations as to whether a reasonable consumer would be misled as regarding added sugars in the Lemonade Soda and Ginger Ale Soda” – whose 35 grams and 32 grams of sugar, respectively, were unlikely to occur naturally in ginger root or lemon juice. She found that the other sodas were closer calls (a reasonable consumer might conclude that the 29 grams of sugar in the Orange Mango Soda, for example, occurred naturally in the orange juice and mango puree listed as ingredients). Nonetheless, she concluded the question of whether a reasonable consumer would have been misled was a question better decided by a jury and on that basis could not be dismissed under Rule 12.

The matter was thereafter voluntarily withdrawn on May 5, 2017, prior to certification. One can reasonably assume the withdrawal was the result of settlement – but because the settlement was pre-certification pursuant to Federal Rule 23(e) and was not a class action resolution — no notice or court oversight was required.

In a similar case involving Steaz flavored ice teas, Swearingen v. Healthy Beverage, LLC, No. 13-CV-04385-EMC (N.D. Cal.), the complaint was filed on September 20, 2013, and followed the same allegations of the Santa Cruz case. On June 11, 2014, Judge Chen stayed the matter pursuant to the primary jurisdiction doctrine. The stay was lifted on July 22, 2016, and on October 31, 2016, Healthy Beverage moved to dismiss. The Court ruled on the motion on May 2, 2017, finding for the defendant.

Website Disclosure. Judge Chen found (in some respects) the opposite of Judge Illston in the Santa Cruz case on this issue of whether disclosure of the sugar content in the product negates whatever confusion may arise from ECJ labelling. Healthy Beverage argued that, because it stated on its website [but not on its packaging] that “cane juice is natural sugar,” and plaintiffs’ counsel acknowledged that the plaintiffs “may have looked” at the website, , plaintiffs could not have been under any illusions that ECJ is anything but sugar. Plaintiffs’ counsel at the motion hearing answered that plaintiffs “did not focus” on that information on the website. Judge Chen did not consider this qualification sufficient,, finding that whether or not the plaintiffs “focused” on Healthy Beverage’s disclosure, they conceded that they read it and, therefore, reliance on the packagaging’s ECJ label was not reasonable.

Reese v. Odwalla, Inc., No. 13-CV-00947-YGR (N.D. Cal.) followed the same path as the previous two cases – a Complaint filed in 2013, stayed in 2014, and revived in 2016 after FDA released its ECJ guidance. The product is Coca-Cola’s Odwalla brand smoothies and juices labelled with ECJ. On October 10, 2016, a motion to dismiss was filed by Odwalla that the Court ruled on in February of 2017:

Premption: The crux of Odwalla’s motion to dismiss was express federal preemption. Odwalla argued that, where the FDCA provides that “no State . . . may directly or indirectly establish under any authority . . . any requirement for a food . . . that is not identical to such standard of [the FDCA]” (21 U.S.C. § 343-1(a)(1)) and the FDA’s guidance on the use of the term ECJ only became final in August 2016, there were no laws prohibiting the use of ECJ prior to the issuance of the 2016 Final Guidance. Thus, the retroactive imposition of such prohibition would amount to an imposition of non-identical labeling requirements and would therefore be preempted (citing to Wilson v. Frito-Lay N. Am., Inc., 961 F. Supp. 2d 1134, 1146 (N.D. Cal. 2013) (finding that retroactive application of FDA’s clarification of an ambiguous regulation would offend due process); Peterson v. ConAgra Foods, Inc., No. 13-CV-3158-L, 2014 WL 3741853, at *4 (S.D. Cal. July 29, 2014) (finding that federal law preempted state claims based on labels prior to FDA’s clarification of labeling requirements). Judge Rogers rejected this argument, noting that neither the 2009 Draft Guidance nor the 2016 Final Guidance announced a new policy or departure from previously established law. Judge Rogers reasoned that FDA merely confirmed that ECJ fits the definition of sucrose under the regulations, and, therefore, needs to be labeled as “sugar.” Thus, the Court found that the State law claims did not contradict Federal law and were not preempted. This same preemption argument was also rejected in Swearingen v. Late July Snacks LLC, No. 13-CV-04324-EMC, 2017 WL 1806483, at *8 (N.D. Cal. May 5, 2017).