** Monsanto Gets its First Victory in the Battle over Herbicide Prop 65 Listing **

By: Brent E. Johnson

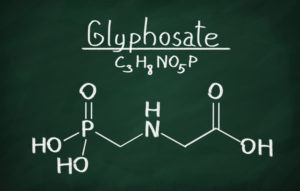

Background: Glyphosate is a molecule that inhibits a biological process only found in plants (not humans and animals). The compound was discovered by a Monsanto chemist in 1970, then patented and brought to market in 1974 as “Round Up.” Initially, the product was only used on a small scale, because, while it is toxic to most weeds, it also kills most crops. However, when Monsanto developed and began introducing genetically modified crops engineered to be resistant to the herbicide (“Roundup Ready” crops), the chemical was able to be used on a broad scale. As a result, the chemical’s use skyrocketed — at the same time that overall herbicide use dropped. In 1987, only 11 million pounds of Round Up were used on U.S. farms – now nearly 300 million pounds are applied each year. A study published in 2015 in the journal Environmental Sciences Europe found that Americans have applied 1.8 million tons of glyphosate since its introduction in 1974. Worldwide, the number is 9.4 million tons. That is enough to spray nearly half a pound of Roundup on every cultivated acre of land in the world. Round Up and Round Up Ready products are worth many billions of dollars.

California’s Office of Environment Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) announced a proposed listing of glyphosate as a Prop 65 chemical on September 4, 2015. The effect of glyphosate’s listing under Prop 65, cannot be underestimated as there are detectable levels of glyphosate in virtually every part of the food chain. Monsanto is famously vigilant in protecting its rights – for example in protecting its crop patents. So when OEHHA proposed the listing, it was inevitable that litigation would follow.

On January 21, 2016, Monsanto struck. It filed a petition in Superior Court in Fresno County seeking injunctive and declaratory relief to enjoin OEHHA from listing glyphosate as a Prop 65 chemical. It did so on the basis of its allegation that the listing mechanism violated the California and United States Constitutions. See Monsanto Co. v. Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, No. 16-CE CG 00183, (Sup. Cal.) That is, primarily, Monsanto complained about how its product came to be added to the list.

Under Cal. Health & Safety Code § 25249.8 (b), which cites to Cal. Lab. Code § 6382 (b)(1), “at a minimum” the Prop 65 list must include those “[s]ubstances listed as human or animal carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).” IARC, based in Lyon, France, is an intergovernmental agency, part of the World Health Organization. In March 2015, IARC issued a report labeling the weed killer glyphosate as a “probable carcinogen.” Glyphosate Monograph, Vol. 112, IARC Monographs Series (IARC, 2015b). That report is not without controversy — for example, the EPA has more recently issued its draft human health risk assessment which concludes that glyphosate is not likely to be carcinogenic to humans. Nevertheless, OEHHA has interpreted § 25249.8 (b) to provide that once IARC lists a chemical, it is mandatory for them to do so also. OEHHA duly noticed its intent to list, prompting the lawsuit.

Monsanto raised four arguments, all ultimately rejected by the trial court.

- First, Monsanto argued that OEHHA unconstitutionally delegated its authority to the IRAC by relying on its assessment that glyphosate is a probable human carcinogen. The doctrine of nondelegation is the rather esoteric theory that one branch of government must not authorize another entity to exercise the power or function that it is constitutionally authorized to exercise, itself. Under California law, this doctrine is not offended if the legislature determines the overarching legislative policy and leaves to others the role of filling in the details. Monsanto Co. v. Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, 2017 WL 3784247 (Cal.Super.) citing Kugler v. Yocum, 69 Cal.2d 371, 375-376 (Cal. 1968). On that point, the court stated that the Prop 65 listing mechanism does not constitute an unconstitutional delegation of authority to an outside agency, since the voters and the Legislature have established the basic legislative scheme and policy and it was permitted to leave the “highly-technical, fact-finding” to the IARC (and other authoritative bodies referred to in the Act).

- Second, the court rejected Monsanto’s due process claims. It held that due processrights are only triggered by judicial or adjudicatory actions. California Gillnetters Assn. v. Department of Fish & Game, 39 Cal.App.4th 1145, 1160 (Cal. 1995). The court stated the Prop 65 listing was not adjudicative, but a “quasi-legislative act.”

- Third, the court rejected Monsanto’s arguments that the listing process violated California’s Article II, Section 12, which prohibits private corporations from holding office or performing legislative functions. It found that there are no facts that would tend to indicate that the IARC is a “private corporation,” or that IARC has an pecuniary interest in being given the power to name certain chemicals on its list of possible carcinogens.

- Fourth, the court gave short shrift to Monsanto’s claim that listing glyphosate would violate its right to free speech under the California and Federal constitutions, in particular the inherent protections for commercial speech from unwarranted governmental regulation. The court held that the First Amendment claim was not ripe for adjudication because the mere listing of glyphosate does not in and of itself require Monsanto to provide a warning and it may never be required to give a warning.

Monsanto appealed this ruling. It also sought a stay of the trial court’s decision pending its appeal, The appellate court and the California Supreme Court rejected these requests for a stay in June 2017. OEHHA wasted no time after the Supreme Court’s decision adding glyphosate to the list on July 7, 2017. After this ruling, subject to the substantive appeal of the trial court decision, July 7, 2018 was to be the date by which companies must comply with the Prop 65 requirements for glyphosate.

Not content to wait idly by, Monsanto moved the battle to Federal Court, On November 15, 2017, it filed a complaint for declaratory and injunctive relief in the Eastern District of California (No. 2:17-cv-02401-WBS-EFB) together with the National Association of Wheat Growers, National Corn Growers Association, United States Durum Growers Association, Western Plant Health Association, Missouri Farm Bureau, Iowa Soybean Association, South Dakota Agri-Business Association, North Dakota Grain Growers Association, Missouri Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Associated Industries of Missouri and the Agribusiness Association of Iowa. So far, the following have also signed on as amicus – the State of Wisconsin, South Dakota, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Michigan, Kansas, Louisiana, Iowa, Indiana, Idaho and Missouri.

The complaint starts by attacking the IARC listing, noting that a dozen other global regulatory and scientific agencies have found no link between glyphosate and cancer. The allegedly “false” warning under Prop 65, plaintiffs argue, compels speech violating Plaintiff’s First Amendment rights. Plaintiffs also argue that the listing and warning requirement conflict with, and are preempted by Federal legislation,notably the United States Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) and Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA). The complaint also raises the issue rejected by the state court that the listing process violates the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Plaintiffs filed a Motion for Preliminary Injunction on December 6, 2017, which was heard on February 20, 2018. On February 26, 2018, U.S. District Court Judge William B. Shubb ruled in favor of Monsanto and the other named plaintiffs. No. CV 2:17-2401 WBS EFB, 2018 WL 1071168, at *1 (E.D. Cal. Feb. 26, 2018). The order declined to go so far as to remove glyphosate from the Proposition 65 list, but at least for now, bars the State of California from imposing the corresponding warning requirement while the case challenging its listing proceeds on the merits.

The court primarily relied on Monsanto’s First Amendment argument in issuing the injunction. Judge Shubb concluded that, to the extent Prop 65 necessitates warnings for glyphosate, California is in essence compelling commercial speech. The court held that the government may only require commercial speakers to disclose “purely factual and uncontroversial information” about commercial products or services, as long as the “disclosure requirements are reasonably related” to a substantial government interest and are neither “unjustified [n]or unduly burdensome.” Id. at * 5 citing Zauderer v. Office of Disciplinary Counsel of Supreme Court of Ohio, 471 U.S. 626, 651 (1985); CTIA-The Wireless Ass’n v. City of Berkeley, 854 F.3d 1105, 1118 (9th Cir. 2017).

In this case, the court held that the link between cancer and glyphosate was not uncontroverted – particularly where “only one health organization had found that the substance in question causes cancer and virtually all other government agencies and health organizations that have reviewed studies on the chemical had found there was no evidence that it caused cancer.” Id. at *6. The court went further stating, “[u]nder these facts, the message that glyphosate is known to cause cancer is misleading at best.” Id. Accordingly, it was determined that the balancing of interests involved weighed in favor of restraining the enforcement of the warning requirement for glyphosate while the remainder of the case was decided.

The court enjoined “defendants” (i.e. OEHHA and the California Attorney General) and “their agents and employees, all persons or entities in privity with them, and anyone acting in concert with them.” Id. at *8. We will see if private Prop 65 bounty hunters consider themselves bound by this injunction.

One area the dispute will also move to is the No Significant Risk Levels (NSRLs) for glyphosate. If the NSRL is set at a particularly high level (perhaps based on the factual controversies referred to above), then the issue over listing may be mooted. Again, however, a sky high NSRL still may not dissuade Prop 65 bounty hunters.