What is CBD?

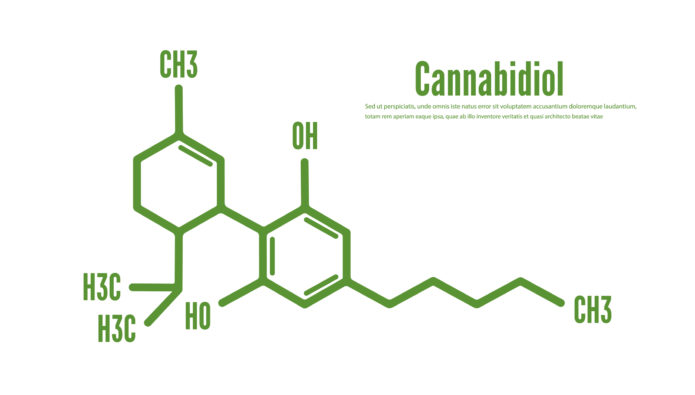

As if you don’t know! Cannabidiol (CBD) is an extract from the Cannabis sativa L. plant. When the cannabis plant is hemp, the CBD derived from it should contain only negligible amounts of THC – the chemical compound that produces a high. CBD, however, can also be extracted from the marijuana plant, and this CBD, of course, contains higher quantities of THC. No matter which type of cannabis plant CBD is derived from, it’s pharmacologically active in its own right, and has been studied as a treatment for diseases such as MS and epilepsy. CBD is also thought to have general beneficial uses for pain relief and as an anti-inflammatory. On that basis, it has gained popularity in the last few years as an additive to foods, beverages and dietary supplements. Last year, CBD consumer sales in the US were over $350 million. Some projections indicate that by 2020 that figure will surpass $1 billion. Mainstream companies are eager to jump in – including Carl’s Jr., which tested a CBD burger – “The Colorado High” — albeit only for one day and only in marijuana-friendly Colorado.

Is It Legal to Sell Food, Beverages or Dietary Supplements that Contain CBD?

Nope – although the basis for its illegality has changed over time.

In the Beginning.

Until recently, the Drug Enforcement Agency made no distinction between a cannabis plant that is high in THC and grown for its psychoactive properties (a/k/a “marijuana”) and a low-THC plant (“hemp”) grown for other uses, including as a food additive, in the form of hemp seeds and hemp cake, for example. Hemp was lumped in with marijuana as a Schedule I drug by DEA, and, therefore, it could not be legally sold in the United States. An anomaly existed in the Ninth Circuit, however, where the Court of Appeals held back in 2004 that DEA “cannot regulate naturally occurring THC not contained within or derived from marijuana – i.e., non-psychoactive hemp products – because non-psychoactive hemp is not included in Schedule I.” Hemp Indus. Assoc. USA LLC, et al. v. DEA, 357 F.3d 1012 (9th Cir. 2004). Unfortunately for the nascent hemp consumables industry, the Ninth Circuit affirmed DEA’s authority to prevent the cultivation of industrial hemp anywhere and everywhere in the United States. And, since DEA did not seek a writ of certiorari before the U.S. Supreme Court, the Ninth Circuit’s decision did not become the law for the entire country.

Federal Legislative Baby Steps.

Things started loosening up for hemp in 2014. Section 7606 of the 2014 Farm Bill authorized state pilot programs for growing industrial hemp, which included the right to “market” the products created from those programs. In 2016, Congress defunded any effort by DEA to crack down on hemp products developed through state pilot programs in The Consolidated Appropriations Act – meaning that hemp had an unimpeded (although legally murky) path to market.

The 2018 Farm Bill Passes!

The Hemp Farming Act (S. 2667) (included in the Senate version of the 2018 Farm Bill) made the big change hemp farmers and CBD activists had long been hoping for – defining “hemp” as different from “marijuana.” Hemp was no longer a controlled substance — just an agricultural commodity. The definition (Sec. 297A (1)) provides that hemp is cannabis that contains no more than 0.3% THC by dry weight. On December 20, 2018, President Trump signed the 2018 Farm Bill into law.

In addition to clearly articulating that hemp is not a Schedule I controlled substance, the Hemp Farming Act places federal regulatory authority of hemp with USDA but allow states to regulate hemp cultivation. It also removes restrictions on banking, water rights, and other regulatory roadblocks the U.S. hemp industry faces and explicitly authorizes crop insurance for hemp.

On the agricultural side, the 2018 Farm Bill does not mean that hemp will immediately become a cash crop or that farmers can grow it as freely as they do corn, soybeans, or wheat. Because hemp and marijuana are both versions of the cannabis plant, a stricter regulatory regime is necessary to prevent hemp from “growing rogue.” Before hemp can be grown (outside of a 2014 Farm Bill pilot program as discussed above), the state in which it is grown must create – and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) must approve – a plan under which the state will monitor and regulate production. See 7 U.S.C.A. § 1639o – 1639s.

Each state regulatory plan must include a practice for maintaining information regarding the land where hemp is grown, a method for testing THC concentration, a protocol for disposing of plants and products produced in violation of the law, and a procedure for ensuring that the state will take appropriate actions for violations of federal hemp laws. In states that do not devise their own regulatory programs, the USDA will create a federal licensing scheme. One year after the USDA creates its plan, the provisions of the 2014 Farm Bill that authorized pilot programs for industrial hemp will be repealed so that all hemp will be grown under the auspices of a full-blown state or federal regulatory scheme. Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue said during a congressional hearing in February that USDA is working to create that regulatory framework in time for the 2020 growing season.

Kentucky submitted its oversight strategy for hemp production on the same day the 2018 Farm Bill passed and is waiting for USDA approval. Pennsylvania and Tennessee quickly followed suit.

FDA Weighs In.

The 2018 Farm Bill is a real step forward for hemp cultivation. But growing hemp is one thing. Making foods and supplements out of hemp-derived CBD is quite another. On the same day that the 2018 Farm Bill was signed by President Trump, then-FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., issued a statement that FDA has full authority to regulate products containing cannabis or cannabis-derived compounds under the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act and that it will treat those products as it does any other FDA-regulated product. Dr. Gottlieb first mentioned FDA’s concern that CBD products are being marketed to consumers by supplement companies as drugs – i.e., with therapeutic claims. This wasn’t too bad — legitimate supplement companies know when their claims are out of bounds. But then Dr. Gottlieb dropped the hammer: Because CBD is an active ingredient in an FDA-approved drug (Epidiolex – an anti-seizure medication approved in 2018), it’s a drug and can’t be introduced into food or sold as a dietary supplement. Period.

FDA’s Next Steps.

- In a January 15, 2019 letter, Oregon’s senators urged FDA to take action to update federal regulations to permit the use of CBD in food.

- During a February 28 hearing with the House Subcommittee on Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies, Committee on Appropriations, Commissioner Gottlieb announced he was putting together a working group to consider doing just that.

- On April 2, 2019, FDA released a statement from Commissioner Gottlieb that announced that the Agency will create a high-level internal working group to explore potential pathways for dietary supplements and/or conventional foods containing CBD and other cannabis-derived ingredients to be lawfully marketed, including a consideration of what statutory or regulatory changes might be needed and what the impact of such marketing would be on public health.

- On May 31, 2019, FDA held its first public hearing on CBD. The public hearing was webcast (a first!)

- Commissioner Sharpless maintained that, while there has been an explosion of interest in products containing CBD, there is still much that we don’t know: “For example, how much CBD is safe to consume in a day? What if someone applies a topical CBD lotion, consumes a CBD beverage or candy, and also consumes some CBD oil? How much is too much? How will it interact with other drugs the person might be taking? What if she’s pregnant? What if children access CBD products like gummy edibles? What happens when someone chronically uses CBD for prolonged periods?”

- He noted that FDA is aware that companies appear to be marketing products containing CBD that violate federal law and stated, “[T]he agency does not have a policy of enforcement discretion with respect to any CBD products.” Signaling, perhaps, that FDA does not intend to turn a blind eye.

- Also clear from his comments, “FDA is taking an appropriate, well-informed, and science-based approach to the regulation of . . . CBD.” Meaning anecdotal evidence is not going to cut it – and it may be a while.

- FDA has established a docket for public comment on this hearing. The docket number is FDA-2019-N-1482. The docket will close on July 2, 2019.

- On June 21, 2019 the House of Representatives included in the House Appropriations Bill an earmark of $100,000.00 for FDA to study the issue of what an appropriate upper limit for CBD daily exposure would be – a critical question needed to establish standards for CDB in food and supplements. At the same time the House approved a rider to the fiscal year 2020 Commerce-Justice-Science spending bill which specifically prohibits the Department of Justice from using funds to prevent states, Washington, D.C., and U.S. territories from implementing their adult-use and medical marijuana programs.

What about topical CBD products?

The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act only applies to products “intended for ingestion.” 21 U.S.C. 321(ff)(2)(A). CBD topical creams and gels are not ingested, so can they be legally sold in the United States? The answer to this straight-forward question is far from certain, but the short answer is that it may depend on their intended uses. If a topical product is claimed to have a therapeutic or medical use, then it is by definition a “drug.” 21 U.S.C. 321(g)(1). FDA pre-approves prescription drugs and pre-approves the “recipe” for non-prescription over the counter (OTC) drugs under its OTC monograph program. Aside from Epidiolex, there are no prescription drugs with CBD that are FDA-approved and CBD is not an ingredient that has been considered under the OTC monograph process. Simply put, besides Epidiolex, CBD is not permitted in drugs, included OTC topical lotions.

What if the intended use is cosmetic? A cosmetic is defined under the FD&C Act as an article “intended to be rubbed, poured, sprinkled, or sprayed on, introduced into, or otherwise applied to the human body or any part thereof for cleansing, beautifying, promoting attractiveness, or altering the appearance.” (21 U.S.C. 321(i)). Unlike drugs, cosmetic ingredients are not subject to premarket approval by FDA (except for most color additives). But most CBD oils and lotions do not appear from their marketing claims to be limited in their intended use to beautifying the body and might be hard pressed to call themselves cosmetics.

What about State law?

It is important to note that the 2018 Farm Bill preserves the authority of States to enact and enforce laws regulating hemp that are more stringent than federal law. States cannot block legitimate interstate shipments of hemp, but they can enforce their own laws with respect to hemp products. Bear in mind, this is an issue that has already been decided in some states as they have already either legalized all marijuana products or enacted a narrower legalization of CBD products. But some states have done neither. Thus in May 2019, a Tennessee woman was arrested and booked into jail on a possession of hashish charge at Disney World after her bag was searched on her way into The Most Magical Place on Earth. The 69-year old grandmother had a container of CBD oil in her purse, which she used for joint pain. Although the prosecutor ultimately decided not to pursue the matter, the Orange County Sheriff’s Department issued a statement that her arrest was lawful because “possession of CBD oil is currently a felony under Florida State Statute.” In other states, notably New York, Ohio, and Maine, embargoes on certain products containing CBD are in place. Police in Texas have raided stores and seized CBD products.

Are Mainstream Companies Pushing Ahead Nonetheless?

Many companies are. Kroger, for example, recently announced that it will begin selling CBD lotions, oils and other products in 17 states. Kroger joins Sheetz, Walgreens Boots Alliance, and CVS Health Corp as a topical CBD product retailer (although the trend is not all in that direction, one national on-line grocer (Thrive Market) has pulled CBD products from its offerings). Of course, the CBD products they sell can’t carry dietary supplement claims and certainly can’t make therapeutic claims and cannot be a food. And they will have to steer clear of certain states. Whether these companies will be able to navigate that narrow legal path – and whether the FDA will ultimately get in their way remains to be seen.

Can I use the US Postal Service to send CBD products to customers?

The U.S. Postal Service (USPS) confirmed on June 6, 2019, that it will permit hemp and hemp-based products in domestic mail. According to its revised Publication 52, Section 453.37 a CBD product that meets the 0.3 THC threshold and otherwise complies with all applicable federal, state, and local laws pertaining to hemp production, processing, distribution, and sales are deemed to be mailable. The policy notes that mailers are responsible for compliance with these laws, and under postal service regulations must retain records establishing compliance, including laboratory test results, licenses, or compliance reports, for no less than 2 years after the date of mailing.